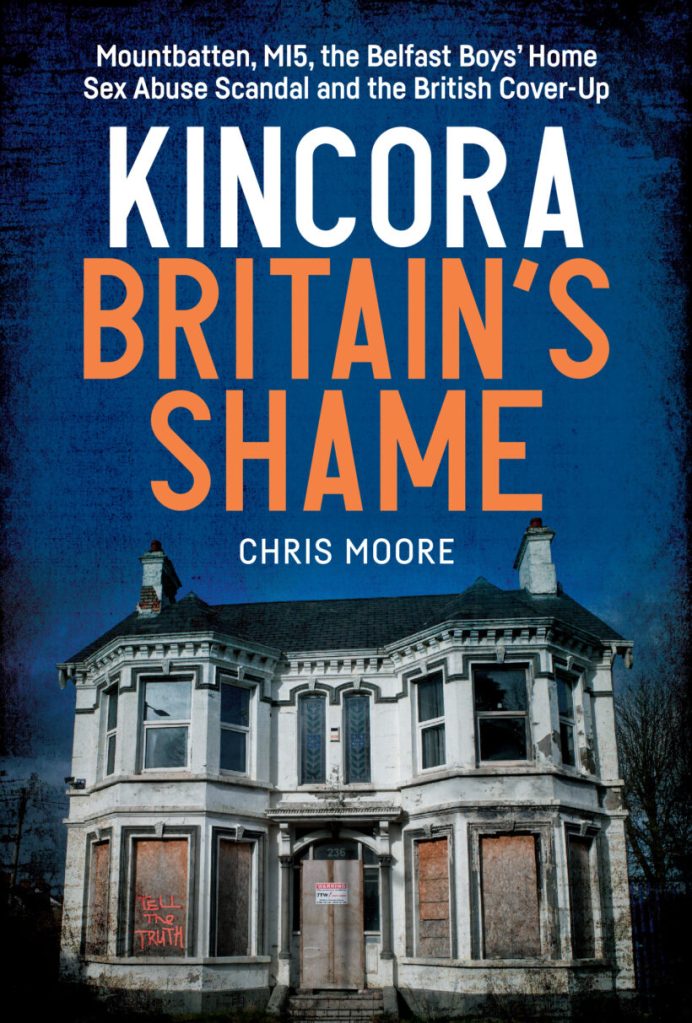

Belfast Child Abuse Scandal : KINCORA MONSTER DENIED ALL WHEN CONFRONTED BY AUTHOR IN THIS EXTRACT FROM HIS NEW BOOK, KINCORA: BRITAIN’S SHAME

Child Abuse remains a major crime problem in Ireland, on both sides of the border. Veteran reporter Chris Moore has worked tirelessly researching the issue, and fighting state censorship.

Governments running the two bits of Ireland must stop pocketing knowledge of abuse, and then using the information for political intelligence purposes, and protecting powerful wealthy criminals.

The building at the centre of the scandal was demolished three years ago, but the cover up of the crimes committed behind its walls continues.

Suzanne Breen, Journalist, Belfast

It is long past the time that the full truth was told about what happened in the house of horrors.

McGrath denied his sins to the end – one of his last interviews

Chris Moore, Sunday Life, May 18th, 2025

Source : “McGrath Denied His Sins to the End” Kincora Monster Denied All

KINCORA MONSTER DENIED ALL WHEN CONFRONTED BY AUTHOR IN THIS EXTRACT FROM HIS NEW BOOK, KINCORA: BRITAIN’S SHAME

I parked in the forecourt of a neighbourhood shop with the intention of asking if anyone could direct me to McGrath’s home.

I presented a few items for payment, casually asking the shopkeeper if she could point me in the direction of his house.

Politely, but firmly, she declined, saying that as far as she and others in the village were concerned, ‘Billy’ McGrath was a friendly man who said he had been badly wronged in the courts and pestered by reporters.

“I suppose you are one of them,” she said bluntly. I owned up and then respectfully suggested that the evidence that convicted him indicated that, far from being wronged, McGrath had actually got off very lightly.

Collecting my change, I headed out to the car to consider my next move. I could do the door-to-door routine, but the attitude of the shopkeeper suggested I would receive little cooperation. Then, an elderly man approached, wearing a cardigan, dark trousers and slippers, so obviously he had not travelled too far.

I got out of the car and watched as he moved towards the shop. There is a God, I thought. Gingerly I edged around the car, proffering my hand as he reached me.

He accepted, we shook and I announced myself as “Chris Moore from the BBC”. McGrath smiled wryly and told me he had nothing to say.

“Don’t you want to defend yourself, your good name?” He replied that he had been pestered by reporters in recent times and had received six offers from newspapers for his version of the Kincora story.

For the next 15 or 20 minutes, though, he stood his ground and said more than either he or I had expected. I had never met McGrath before, yet nine years of gathering information on him had created the illusion in my head that I was familiar with the man.

Now, for the first time, I had the opportunity to witness for myself the oratorical abilities that former friends and colleagues had described.

It was easy to understand how he had been able to survive for so many years undetected, how he had an ability to lead his life in several different compartments at once.

Above all, I was amazed at how plausible he could make it all sound. Had I not known the truth about so much of his life, he might well have succeeded in persuading me of his innocence.

callous

I tried to imagine him giving a talk in a room packed with Orangemen or evangelical Christians, while at the same time remembering the callous way in which he had (abused the boys).

But I was here to listen, to ask questions and to report what McGrath had to say to a public waiting to hear from a man I had helped to demonise by my coverage of Kincora.

From the outset McGrath was adamant that he would not do an interview for television, not even on audio tape, even to attempt to clear his name. “I have my loyalties,” he said by way of explanation. “The truth of Kincora has not yet come out,” he said intriguingly. “Any intelligent man can tell that, for in spite of all the millions of words written and spoken about it so far, no one has been told the truth. I and I alone can tell the true story of Kincora.”

But no amount of persuasion could convince him to talk. Then he hit me with, “If I were to tell the truth about Kincora it would be told without the use of one word … sex! That word would not feature at all.”

What about the long list of witnesses who would use the word sex?

“I am aware of that.”

I told him I had seen the statements made against him.

“So have I,” he replied.

“But I have spoken to some of the young men who made statements and they have told me you sexually abused them.”

“If that is what you want to believe,” he responded.

Why would anyone want to fit him up for criminal activities if he was not guilty? How could so many different people join together in such a conspiracy?

There was no response.

I pressed ahead. “What about the medical report? The doctor said you were a classic example of an active homosexual?”

“I know, I have seen that as well,” he said.

I said it was difficult to believe that all those people would suddenly decide to tell lies about him in some enormous conspiracy.

Lisburn

He turned as he reached the shop door and said, “You know, there are wheels within wheels. This whole matter does not stop at Lisburn.” He turned and entered the shop.

“Lisburn” was the significant word. It was the town where British Army Headquarters was based and headquarters for operatives in various intelligence-gathering agencies.

I waited outside, wanting to know more. After a few minutes, he stepped out again, and made no attempt to avoid me. Indeed, he seemed as amiable as he had been before he went into the shop.

I asked why (the late Rev) Paisley was so quick to dump him when they had been so closely associated over a great many years.

He denied ever having a “close friendship with Paisley.” Had he not been involved with Paisley through his political activities? Again a denial.

Had he not gone on occasion to meet Paisley? “I never had any personal dealings with Paisley,” he responded.

Now I knew he was telling lies because of the evidence of so many others who clearly remember meetings at Paisley’s church. I realised McGrath’s gameplan was to treat me as someone who did not know as much as I did. It was time to nail down this lie.

Were your children not married in Paisley’s church? Of course, I knew they were because I had the marriage certificates.

“Did your daughter Elizabeth not marry in Paisley’s church?” I asked. He hesitated, but then said, “Yes.”

“And was your son Worthington not married in that same Paisley church?” Again, a slight hesitation before, “Yes. That is right.” “So, you did know Paisley and his church quite well?”

“I never met Paisley on political matters,” he said categorically.

I tried to get back on the Lisburn trail by mentioning all the allegations that had been made in the media over the years about the involvement of British Intelligence in the Kincora affair. He would not respond. I mentioned all the suggestions that he had been working for military intelligence.

I spoke about the police discovering that he had first come to the attention of MI6 back in 1958. This drew a smile but no comment.

I asked him how it would look if he were to die before he put forward his side of the story, but he just smiled. As he got nearer his home, with me still on his shoulder, he expressed the hope that I would not be writing this up for a story. I informed him that I had introduced myself as a reporter for the BBC and that he had talked freely and that, yes, I did intend at some point to use the information in a story.

I watched him walk towards the door of his home, naturally noting the address. We said farewell.

The face-to-face had happened so quickly that it was only as I drove away I realised I had not given McGrath a business card with my telephone numbers, in case, having thought it over, he wanted to get in touch. I headed back, parked and knocked on the front door.

I apologised and explained that I would like to leave my card. Surprisingly, he stopped on the doorstep for another short chat.

This time he got into political speech mode, expressing the view that the world was changing, in a state of flux. Ireland, he told me, would in the next 10 or 15 years become a very different place.

“There will be big changes,” he emphasised, “some amazing changes.”

cause

He repeated that his loyalties were to the cause he had served all his life: to Northern Ireland and to Ireland the island.

He looked ahead to 1992 when changes in Europe would effectively remove national border restrictions.

His political work, he declared, was the real reason for what he described as “the persecution of Billy McGrath”.

Then he asked, “Why is Billy McGrath being persecuted? If I was a homosexual and if I had sex with all the boys I am supposed to have had, why persecute me?

“There are thousands out there in the world having homosexual relations every day and there is not a word about it. So why pick on me?

Why not Joe Mains or Raymond Semple (his fellow convicted Kincora staff members)? They have picked on me not because of who I am, but because of the cause I represent.”

I mentioned to McGrath that I had seen a document published in 1986 relating to the Anglo-Irish Agreement, which had been signed at Hillsborough in November 1985 by the British and Irish prime ministers.

This document, I said, was printed by Tara (a far-right loyalist paramilitary group he founded).

He admitted it was his work and, asking me to wait, went inside and returned with the document in his hand.

He handed it to me as I moved back into the question of British Intelligence involvement in Kincora. Could he offer guidance as to whether there was any substance to the claims about British Intelligence?

Before answering he sought an assurance (which was given) that what he was about to say would not be quoted as it would “make me out to be a liar with the other reporters who had called”.

Given that McGrath is now dead, I feel I am released from this undertaking.

The answer he gave was: “The first I knew of Kincora was when I came home one evening and the Sunday World was thrown down in front of me.”

Given that the story broke originally in the Irish Independent, I was a little confused.

Did he mean this was the first time a story had been written about British Intelligence and Kincora?

Just when he was getting interesting, McGrath seemed suddenly to realise that he was getting drawn in too deeply and he declined to explain any further.

In my car I took another look at the four-page pamphlet ‘Issued by the Tara Group’.

I had seen it before, but now I could see that it represented everything I knew to be true about McGrath.

Even after his imprisonment, he was clearly back to his old ways, with a few loyal supporters to stand by him and keep the name of Tara alive.

This 1986 document on the Anglo-Irish Agreement had the feel of a self-penned epitaph. Indeed, McGrath died on December 12, 1991 — one day after celebrating his 75th birthday and nearly two years after we met in Ballyhalbert.

Chris Moore’s book Kincora: Britain’s Shame is on sale now priced £17.99 (Merrion Press)

A very British scandal… King’s uncle, MI5 and a sordid Kincora cover-up

Suzanne Breen, Sunday Life, June 18th, 2025

The contrast couldn’t be greater between Lord Mountbatten and the boys he allegedly abused. He was a pillar of the British establishment, and they are victims of it.

Mountbatten was born into a life of privilege and luxury. He was the second son of Prince Louis of Battenberg and Princess Victoria of Hesse and by Rhine.

His godparents were Queen Victoria and Nicholas II of Russia. He joined the Royal Navy during the First World War, and afterwards attended Christ’s College, Cambridge.

He was Supreme Allied Commander South East Asia during World War Two, and later the last Viceroy of India.

Arthur Smyth’s life was very different. His father worked in the shipyard, but spent all his money in the pub.

‘I thought I’d landed in heaven’

Arthur and his eight brothers and sisters grew up in squats, some of which had no running water. They moved around constantly. Belfast, Larne, Carrickfergus and Greenisland were among the places the children briefly called ‘home’.

When Arthur was 11, he’d been at 13 schools. His parents’ marriage broke up in the summer of 1977. The kids were split and dispatched to different children’s homes by the courts. Arthur was sent to Kincora.

At first, he adored the white detached villa on the Upper Newtowards Road. He’d never lived in a house that big which had a garden with trees to climb and a majestic banister to slide down.

He was now fed regularly: three decent meals a day. “I thought I’d landed in heaven,” he recalls. Housemaster William McGrath “looked like an old granddad”. And then the child woke up one night to find McGrath in his bedroom. The paedophile raped him.

Arthur’s story is powerfully recounted in journalist Chris Moore’s new book Kincora: Britain’s Shame. McGrath told the boy that if he didn’t keep quiet about the abuse, he’d never see his siblings again. “I didn’t know anything about sex. I was in pain for days,” he recalls.

“McGrath just walked away, leaving an 11-year-old boy in pain,” Moore writes.

It was far from the end of Arthur’s hell. One day, McGrath found the child playing on the staircase and told him he wanted to introduce him to his “friend Dickie”.

Moore says the boy was ordered to “look after (Dickie) in the same way he looked after McGrath”. After the royal raped him, Arthur says he was told to take a shower. A few days later there was “a repeat of what had happened at their first meeting”, Moore writes.

The journalist has interviewed two other boys who allege they were also raped by Mountbatten.

Moore claims that MI5 and the British political establishment have for decades tried to cover up the senior royal’s involvement in a paedophile ring.

He reveals how a detective, contacted by concerned social workers, secretly photographed VIPs visiting Kincora including NIO officials, lay magistrates, police officers and businessmen.

MI5 has a case to answer

The detective requested resources to investigate the home but was ordered to leave the matter by his superiors.

Moore says McGrath worked for MI5, and it’s even possible that he was planted in the children’s home as part of an intelligence-gathering operation. The journalist makes a compelling case that MI5 — at the very least — knew about what was happening and kept quiet.

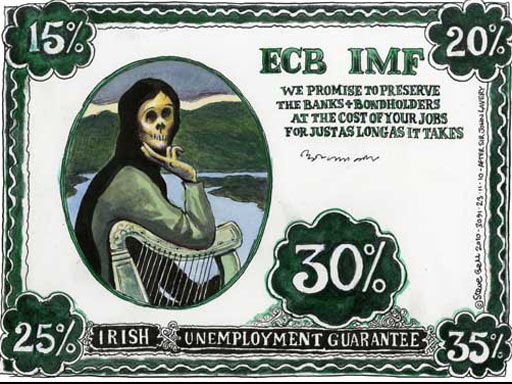

Shamefully, there has been no adequate inquiry into Kincora. Some files have been destroyed, while others have been locked away by the British government to 2065 and 2085.

The most marginalised and vulnerable children were raped by powerful men, allegedly including King Charles’ grand uncle.

The building at the centre of the scandal was demolished three years ago, but the cover up of the crimes committed behind its walls continues.

It is long past the time that the full truth was told about what happened in the house of horrors.

Leave a comment