A series of Tributes to the Investigative Journalist Ed Moloney – “A strong voice against censorship: both that of the state and the more insidious self-censorship that had crept into journalism”

A number of tributes to the investigative journalist Ed Moloney are published below.

Also included is an account of how Ed published sensational evidence about the role of William Stobie (at one time a quarter-master in the loyalist paramilitary Ulster Defence Association), in the political murder of Belfast human rights lawyer Pat Finucane. The British state’s unsuccessful attempt to obtain details of the journalist’s confidential sources were defeated.

It is refreshing to read tributes about about a man I knew well that are kind, affectionate, and that do not pretend Ed was a saint.

He had a short fuse!

Here is one personal example. I knew Ed a little bit before 1998, and followed in great detail his brilliant writing about the 6 county bit of Ireland. Other friends – Ralf Sotscheck, Sandy Boyer, and Patrick Farrelly knew Ed much better than me.

I attended the 1998 Sinn Féin Árd Fheis in the middle of a very bizarre political episode. The “peace process” which gave birth to the Good Friday Agreement was endorsed by 95 per cent of the party’s delegates, but one important obstacle had to be swept aside – Articles 2 and 3 were a part of De Valera’s 1937 Irish Constitution – the ruling class forces demanded support for their deletion. The Unionist veto had to replace Articles 2 and 3 – and that was that. Up to the day of that Árd Fheis SF members insisted they would “never” agree to dropping articles which refused to recognise the legitimacy of the Irish partition settlement – but they did a full monty.

As I observed this political strip-tease Ralf Sotscheck and Ed were nearby discussing events of the day, and I approached Ed intending to praise his excellent writing. Before I had a chance to say a word, Ed launched into a verbal attack, assuming I must be a supporter of the SF leadership. Luckily a startled Ralf Sotscheck cut across the exploding Mr Moloney, and explained that I agreed with most, if not all, of Ed’s analysis.

After that Ed and me became good friends – and maintained regular contact.

John Meehan October 28 2025

Suzanne Breen

Belfast Telegraph October 21 2025

A strong voice against censorship: both that of the state and the more insidious self-censorship that had crept into journalism

When I worked for the Irish Times in Belfast in the 1990s, accounts of Ed Moloney’s tenure as northern editor continued to circulate even though he’d long since departed.

There were stories of verbal confrontations which had sometimes led to the need for office equipment to be replaced.

Moloney’s heated clashes with a Dublin newsdesk he felt had an entirely wrong approach to Northern Ireland were legendary.

It was said that he’d fling the telephone across the office after every impassioned engagement.

Ed Moloney never gave an inch. He was an absolute inspiration to me when I entered journalism. He was a strong voice against censorship: both that of the state and the more insidious self-censorship that had crept into journalism.

He was brave, bold and brilliant. As a journalist, he never occupied the safe, middle-ground. He was always cutting-edge.

His best work came as northern editor of the Sunday Tribune, where he was given free rein.

Moloney didn’t hunt with the pack. He hated when prominent journalists huddled together at the end of a press conference to agree a line.

The idea of safety in numbers was abhorrent to him. He was never afraid to go it alone.

A secret history of the IRA – best book about “our conflict”

His 1986 biography of Ian Paisley with Andy Pollak was superb, but his 2002 A Secret History of the IRA remains the best book ever written about our conflict.

Meticulously researched, it’s a tour de force. It challenges the fallacy that John Hume miraculously convinced Gerry Adams that the IRA’s campaign was wrong.

It charts the republican movement’s slow and steady shift from revolutionary republicanism to constitutionalism.

Every Machiavellian machination of the Adams leadership to bring the IRA to that point is covered.

We follow the journey of Sinn Fein, the party that had once pledged to destroyed the Northern Ireland state, and ended up governing it.

As the author had hoped, his book will have a very long shelf life.

It will be impossible for anyone else writing about the IRA to come anywhere close to it, let alone do better.

Moloney has spoken about the career pressure he faced when he predicted that Sinn Fein would secure between three and seven seats in the 1982 Assembly election.

He said he was treated as a “fellow traveller” for even suggesting that any significant number of northern nationalists would vote for the party. Sinn Fein won 10% of the vote and five seats.

He noted that those in the media who grossly under-estimated the party were never placed under the same pressure because it was perfectly acceptable “to be wrong for the right reasons”.

Moloney railed just as strongly — perhaps even more so — about the censorship that existed post-conflict.

Journalists who reported on grassroots republican dissatisfaction, on splits and divisions within the IRA, and on breaches of its ceasefire were presented as anti-peace.

In Political Censorship and the Democratic State, he wrote: “The practice of not delving too deeply into controversial stories, of asking first what the political and career downside was before pursuing a story or an angle was by now as instinctive to journalists in Ireland as riding a bicycle.

“But now it was the turn of the peace process rather than the war process to benefit from it.

“Before, when the IRA’s war was raging, a journalist would worry about being regarded as a fellow-traveller for writing or wanting to broadcast a story that, for instance, critiques government policy.

“Now they worried about being regarded by officialdom as being ‘unhelpful to the peace process,’ for asking hard questions about its genesis and direction. In the past, republicans, the IRA and Sinn Fein were the principal victims of censorship; now they became its main beneficiary.”

Writer, journalist and press ombudsman in the Republic, Susan McKay, worked with Moloney for over a decade in the Sunday Tribune.

“As a conflict journalist, he was the person to go to. He was fearless and driven by finding out the truth as far as possible,” she said.

“He wasn’t a person to just accept a version of a story told to him by someone with a vested interest. He kept his nose to the ground.

“He did superb work under Vincent Browne’s editorship in the Sunday Tribune. Vincent gave Ed the space to do his stories. Brave decisions were taken under Vincent’s editorship.”

McKay added: “Ed was extremely brave in the way that he stood up for source protection when he refused to hand over his notes to police in 1999. He did a great service to all journalists then.

“Ed could be very helpful and supportive, but he could also thran and turn against you. He bore a grudge like nobody else.

“I felt after he went to the US (in 2000) that he found it hard to leave the northern story behind him.

“I also viewed the Boston College project as deeply flawed.”

A complex character, both gruff and charming

Former BBC Northern Ireland political editor Mark Devenport said: “In the 80s and 90s, when I was a young journalist in Northern Ireland, Ed’s Sunday Tribune articles were required reading.

“He was a journalist who worked his contacts in an intense and solitary way. His weekly pieces often told us something we didn’t know was going on.

“His contribution to the BBC and other broadcast outlets were always astute and articulate. He gave us a sense of the forces operating behind-the-scenes as opposed to the more superficial day-to-day news.

“He could be so deeply committed to the stories and lines he was pursuing that, if other colleagues didn’t share his perspective, he could be quite dismissive.”

Moloney certainly wasn’t clubbable. He was a complex character. He could be both gruff and charming.

He was courageous and cantankerous. He wasn’t a saint, but he was a colossus of Irish journalism.

A colossus of journalism who was not afraid to go it alone or ruffle feathers

Ed Moloney: Secret historian of the IRA and one of Ireland’s ‘most brilliant’ journalists

Obituary: He was author or co-author of several groundbreaking books, including A Secret History of the IRA

Irish Times October 22 2025

Born: 1948

Died: October 17th, 2025

Award-winning journalist and author Ed Moloney, who has died in New York aged 77, was an outstanding chronicler of the Northern Ireland Troubles.

Writing for several outlets during a lengthy career, notably for this newspaper, the Sunday Tribune and, before either, Hibernia and Magill magazines, he was noted for the quality of his sources on all sides of the conflict and, consequently, the authority of the information he provided his readers.

He authored, and co-authored, several groundbreaking books, including the exceptionally detailed A Secret History of the IRA.

In later life, he expanded his work portfolio into TV documentaries, the controversial and ultimately discontinued Boston College Belfast Project, as well as an online blog, The Broken Elbow.

Famously grumpy at times, editors and friends tolerated his occasional mood swings because of the quality of his work. Reactions were tempered also by the knowledge that Moloney endured lasting pain caused by childhood polio and arthritis. He wore leg calipers and walked with the aid of a stick for much of his life.

Edmund (Ed) Moloney was born in England in 1948 and, despite living most of his later life in Ireland and the United States, he never really lost his English accent. He spent some childhood years living with his mother in Alexandria, a small town about an hour northwest of Glasgow, while his father worked away.

Many youthful years were consequently spent living in Germany, Gibraltar and Malaysia before, as a young man, he attended the Queen’s University in Belfast – his introduction to Northern Ireland and all its ethno-political complexities.

He was ferociously forensic. He would give you the story that wasn’t necessarily the story you were looking for – and usually it was better. He had incredible contacts inside republicanism and loyalism

— Matt Cooper

Attracted to the leftist politics of Sinn Féin, the Workers Party, (later transformed into Democratic Left before merging with the Labour Party), he joined the Official IRA, which was then concentrating on political rather than paramilitary activities.

“He was their education officer in south Belfast,” recalls fellow journalist, Belfast resident Hugh Jordan. “He gave short lectures to young people who weren’t really interested in them.”

After a two-year stint teaching English as a foreign language to students in Libya, Moloney returned to Belfast where his interests soon focused on the growing Troubles. He devoted the rest of his career, and life, to reporting those events and their consequences.

Following his death, former Magill editor Vincent Browne described Moloney as “perhaps the most brilliant Irish journalist of the last 50 years”.

What is beyond question is that he was one of a very small cohort of reporters who developed deep and highly placed sources among both republicans and loyalists, and who devoted almost all of their professional lives to reporting the Troubles and their consequences, as opposed to being posted to Belfast for a time before moving on to the next assignment.

“He had superb contacts in the [Provisional] IRA,” says Jordan. “There was no one to touch him in their understanding of this place.”

Moloney was Northern editor of this newspaper from 1980 to 1985 before leaving on unhappy terms. Conor Brady, the paper’s editor from 1986 to 2002, has no doubt, however, as to his significance as a Troubles reporter. “He made a major contribution. He was always extremely well informed and had a very clear strategic perspective over the peace process.”

Moloney moved to the Sunday Tribune as Northern editor from 1987 to 2001, where the weekly news cycle was perhaps more suited to his style of deeply researched and analytical journalism.

“He was ferociously forensic,” recalls former Tribune editor and broadcaster Matt Cooper. “He would give you the story that wasn’t necessarily the story you were looking for – and usually it was better. He had incredible contacts inside republicanism and loyalism.”

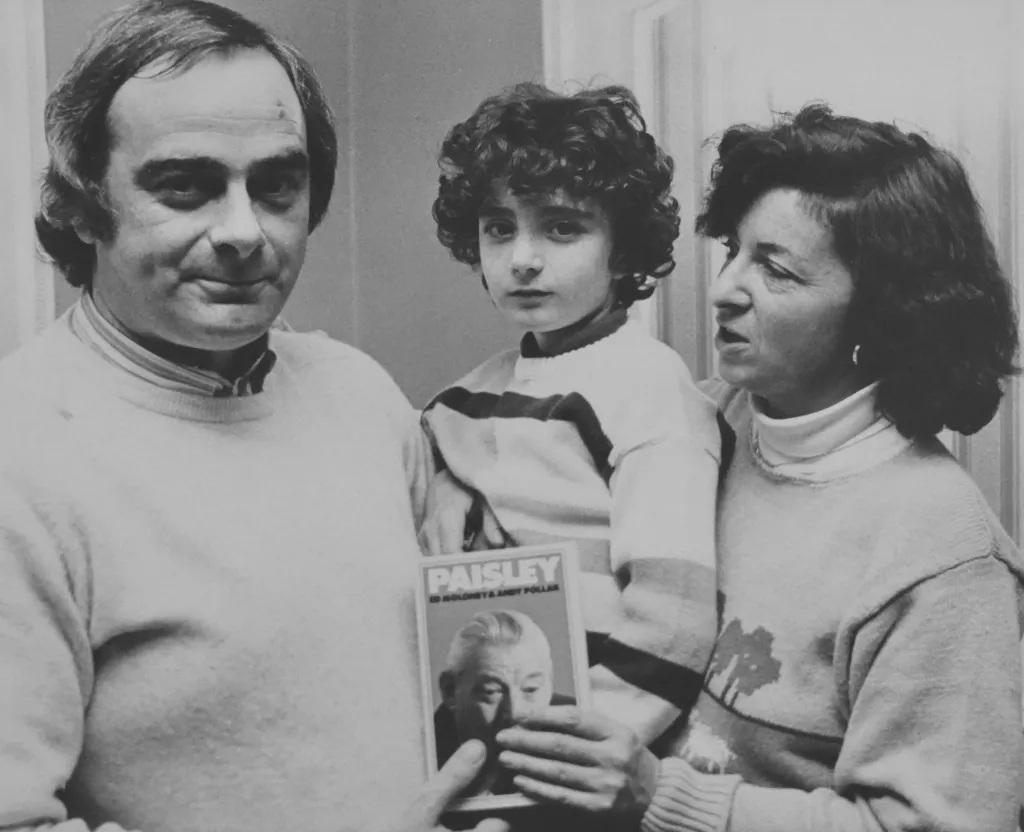

His first book, Paisley, was published in 1986 and was written with former Irish Times colleague Andy Pollak. It stands as an important portrait of the Free Presbyterian Church founder and Bible-imbued-rabble-rousing firebrand preacher Ian Paisley in his “no surrender” days.

A later, solo-authored follow-up volume, Paisley: from demagogue to democrat, traced the DUP leader’s transformation to partner-in-government with Sinn Féin.

But Moloney’s outstanding volume is undoubtedly his groundbreaking A Secret History of the IRA, published in 2002. Over 600 pages, and a further 140 pages of appendixes and source notes, Moloney describes in detail the creation of the modern IRA and the former Sinn Féin president Gerry Adams’s role in it.

While Adams continues to deny he was in the IRA, the book – which he dismissed as “a mixture of innuendo, recycled claims, nodding and winking” – remains in print with those assertions unaltered.

Moloney’s credo as a reporter/writer is perhaps best relayed by a preface to the 2007 edition of the book: “The job of a correspondent, after all, is to inform and increase understanding,” he wrote.

Reviewing that edition, The Guardian newspaper described it as “undoubtedly the best history of Ireland’s … most enduring paramilitary movement ever to be written. It is a brave and mercilessly honest project that will stand the test of time”.

In June 1999, Moloney reported in the Sunday Tribune a version of the murder of Belfast solicitor Pat Finucane, given to him nine years earlier by Ulster Defence Association gunman and police informant Billy Stobie. Police in Northern Ireland got a court order directing Moloney to hand over his interview notes, but he refused to comply.

Moloney moved to the Sunday Tribune as Northern editor from 1987 to 2001, where the weekly news cycle was perhaps more suited to his style of deeply researched and analytical journalism.

“He was ferociously forensic,” recalls former Tribune editor and broadcaster Matt Cooper. “He would give you the story that wasn’t necessarily the story you were looking for – and usually it was better. He had incredible contacts inside republicanism and loyalism.”

His first book, Paisley, was published in 1986 and was written with former Irish Times colleague Andy Pollak. It stands as an important portrait of the Free Presbyterian Church founder and Bible-imbued-rabble-rousing firebrand preacher Ian Paisley in his “no surrender” days.

A later, solo-authored follow-up volume, Paisley: from demagogue to democrat, traced the DUP leader’s transformation to partner-in-government with Sinn Féin.

But Moloney’s outstanding volume is undoubtedly his groundbreaking A Secret History of the IRA, published in 2002. Over 600 pages, and a further 140 pages of appendixes and source notes, Moloney describes in detail the creation of the modern IRA and the former Sinn Féin president Gerry Adams’s role in it.

While Adams continues to deny he was in the IRA, the book – which he dismissed as “a mixture of innuendo, recycled claims, nodding and winking” – remains in print with those assertions unaltered.

Moloney’s credo as a reporter/writer is perhaps best relayed by a preface to the 2007 edition of the book: “The job of a correspondent, after all, is to inform and increase understanding,” he wrote.

Reviewing that edition, The Guardian newspaper described it as “undoubtedly the best history of Ireland’s … most enduring paramilitary movement ever to be written. It is a brave and mercilessly honest project that will stand the test of time”.

In June 1999, Moloney reported in the Sunday Tribune a version of the murder of Belfast solicitor Pat Finucane, given to him nine years earlier by Ulster Defence Association gunman and police informant Billy Stobie. Police in Northern Ireland got a court order directing Moloney to hand over his interview notes, but he refused to comply.

Facing jail for contempt, Moloney refused to budge and eventually, the Lord Chief Justice of Northern Ireland ruled in Moloney’s favour. Shortly after, Moloney was named journalist of the year.

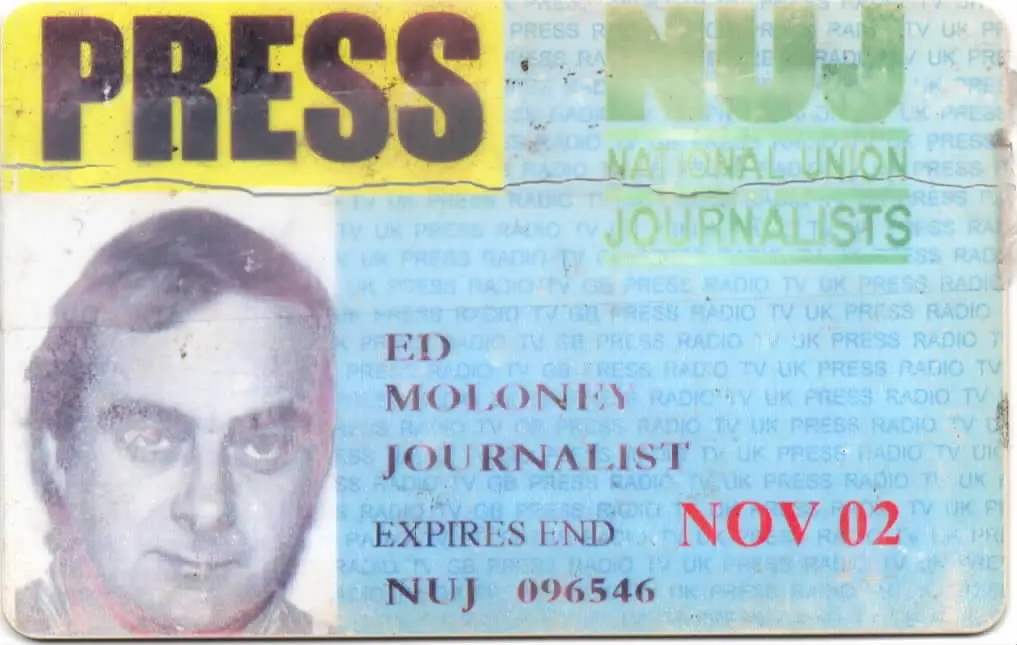

Commenting on his death, National Union of Journalists assistant general secretary Seamus Dooley said Moloney would be remembered for his “courage, dogged determination and unyielding commitment to shining a light into the darkest corners of Northern Ireland’s troubled history … [and standing by] the NUJ code of conduct in refusing to hand over notebooks relating to the Pat Finucane murder”.

In 2000 Moloney moved to New York, partly to help care for the mother of his wife of 50 years, Joan McKiernan, and partly to access pain relief unavailable in Ireland. While living in the United States, he directed Boston College’s Belfast Project, also known as the Boston Tapes, an archive of oral interviews with republican and loyalist militants who had been active during the Troubles.

The project eventually foundered in acrimony over confidentiality agreements and other issues, but material obtained formed the basis of a book, Voices from the Grave, which features interviews from the tapes with IRA man Brendan Hughes and loyalist politician and former UVF member David Ervine.

A documentary titled Voices From the Grave: Two Men’s War in Ireland, which aired on RTÉ in 2010, won the best television documentary prize at the annual Irish Film and Television Awards in 2011.

Donal Fallon

Ed Moloney, who died this week at the age of 77, was one of the most significant authors on the Troubles.

Although we now live in a time when books like Say Nothing are international bestsellers and are adapted for television, Moloney’s pioneering research of paramilitaries took place in a very different political atmosphere.

For Moloney, described rightly by Seamus Dooley of the National Union of Journalists as “one of the most consequential journalists of his generation”, the paramilitary world of which he wrote was not a historical curiosity, but a reality of a political environment he knew well.

Attracted to the left-wing politics of Sinn Féin – the Workers’ Party in his university days and briefly a member of its attached Official IRA – he was later endangered by the same organisation, displeased by his research into its continued and denied activities. Such are the dangers of journalism in war settings.

Moloney’s outstanding legacy is A Secret History of the IRA, his 2002 story of the Provisional IRA. In its preface, he noted: “Had the architects of the 1921 settlement set out to create an inherently unstable entity, they could scarcely have done better than to design Northern Ireland.”

He explained the society from which the Provisionals had emerged, describing the organisation as a “vigorously and rapidly growing infant” within a year of its foundation, quickly overtaking the Officials in scale and ability.

Moloney wrote about the world of paramilitaries without fear. When he found himself questioned in the headquarters of the Ulster Defence Association on spurious allegations that he was working in collusion with republicans, his life was spared and he survived the interrogation. They knew there was no truth to the allegations.

Doomed Belfast Project of Boston College

Yet obituaries of Moloney will focus not only on the importance of A Secret History of the IRA, but on his involvement in the doomed Belfast Project of Boston College, an ill-fated attempt at compiling an oral history of the conflict by interviewing members of republican and loyalist paramilitary groups.

Working in conjunction with Robert Keating O’Neill, the director of the library at the US university, the Belfast Project involved the collection of first-hand testimonies of the Troubles.

Historian and former IRA volunteer Anthony McIntyre was one of those tasked with collecting interviews, while Wilson McArthur conducted interviews with loyalist participants.

It was agreed that interview transcripts would not be released until after the interviewee’s death, with one report noting: “This arrangement was modelled on a similar programme that had been run by the Irish Bureau of Military History [BMH], which recorded the experiences of veterans of the Irish War of Independence and Civil War.”

While the BMH gathered testimonies in the 1940s and 1950s, its statements were not made public until March 2003, long after the events described within had passed firmly into history.

Some of those who gave their memories to the bureau had a sense that the events may all seem quite distant when eyes were eventually laid on them.

“History is for the historian to write,” said Séamus Robinson, one of the men who began the War of Independence in 1919. “Those of us who were involved in the making of our recent history were, and still are, like the storied man in the forest who couldn’t see the wood for the trees.”

In the case of the Belfast Project, the 2010 publication Voices From The Grave, featuring the interviews of deceased men Brendan Hughes and David Ervine, would prove to be the shaking of a hornet’s nest.

Unsurprisingly, the authorities wondered what was contained within other interviews. Subsequent subpoenas from the US Department of Justice, issued at the request of the Police Service of Northern Ireland, would lead to a court battle and eventual arrests.

While the 2014 arrest of Gerry Adams was well documented in the media, the arrest of loyalist Winston Churchill Rea received less attention south of the Border. Charged with the murder of two civilians in 2016 based on the contents of his interview, ‘Winkie’ Rea died in December 2023, before trial.

The Belfast Project was born as an admirable attempt to document personal recollection and important narratives of the conflict. Still, the publication of interviews that carried continuing legal ramifications would prove the undoing of the project and create a deep distrust of oral historians more broadly.

By 2012, Moloney and the men who conducted the interviews were reportedly “strongly of the view that the archive must now be closed down and the interviews be either returned or shredded since Boston College is no longer a safe nor fit and proper place for them to be kept”.

Moloney, furious at the refusal of the college to fight in court, insisted that “Boston College sold us out”.

This all leaves important questions. Is an oral history of the Northern Irish conflict possible? Who should be involved in it?

Oral history has the power to do much good towards reconciliation and in allowing personal healing and reflecting.

John Wilson’s 2019 book, Firefighters During the Troubles, was an important reminder that there are other stories of the conflict to be gathered. If a large-scale oral history of the Troubles is to be undertaken, then, like the Bureau of Military History, it will surely have to remain locked away until the distant future.

An oral history of the troubles would help reconciliation and healing

PRESS RELEASE

Groups express concern on Moloney case

22nd September 1999

The main civil liberties organisations in Britain and Ireland, British Irish Rights W

atch, the Committee on the Administration of Justice, the Irish Council for Civil Liberties, Liberty and the Scottish Human Rights Centre have today expressed serious concern about the action being taken against Sunday Tribune journalist, Ed Moloney.

In a joint statement issued in advance of Mr. Moloney’s application (tomorrow) for judicial review of the decision ordering him to hand over his notes of interviews with William Stobie a spokesperson for the groups said:-

“We are concerned that the two people who have been pursued most vigorously by the authorities are the man who claims that he was a special branch agent at the time of Pat Finucane’s murder and the journalist who published his story. It is disturbing that no action appears to have been taken against those who carried out the murder, those who encouraged it and those who failed to take any action to prevent it or to pursue those responsible for it. We are more convinced than ever that the government should move quickly to establish a fully independent public inquiry.”

“There is no indication that Mr. Moloney is in possession of any more information today than that which the police have had since 1990. The effect of the present action is that both Mr. Moloney’s livelihood and life have been put in jeopardy. In addition the current situation raises serious questions about the freedom of the press and freedom of expression, both of which are vital to a democratic society and protected by Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights.”

For further information contact

Martin O’Brien

John Wadham, Liberty

Donncha O’Connell, ICCL

Press Statement

Issued by Donncha O’Connell, Director, Irish Council for Civil Liberties on Friday 3rd September 1999.

ICCL CONDEMNS DECISION IN ED MOLONEY CASE

The Irish Council for Civil Liberties has joined with the NUJ in expressing the gravest concern about the decision of the Antrim Crown Court in the Ed Moloney case.

Speaking in response to the decision the Director of the ICCL, Donncha O’Connell said: “There is a fundamental misunderstanding of the concept of the public interest at the heart of the judgment. In any democracy the public interest is often served by a healthy tension between the media and state institutions. The idea that the roles of the police and the media are interchangeable is perverse. The ends of democracy are poorly served in a system where journalists are treated as an involuntary wing of the police force”.

He went on to say that the decision of the Antrim Court was difficult to square with the approach adopted by the European Court of Human Rights which emphasises the “chilling effect” of court orders for disclosure by journalists.

In relation to the Moloney case specifically Mr. O’Connell stated: “The enthusiasm of the Stevens Inquiry for getting at Ed Moloney’s notes contrasts sharply with the prior reluctance of UK governments to even concede that the murder of Pat Finucane warranted an inquiry. It is interesting that so much attention has been focused on one journalist who happens to have pursued the case for an inquiry so doggedly. One cannot help speculating that this is some form of retribution”.

Leave a comment