Robert Ballagh’s “The Thirtieth of January”: A Bloody Sunday Painting and the Troubles in the Two Bits of Ireland

In this interview the artist Robert Ballagh discusses the painting “The Thirtieth of January”, depicting Bloody Sunday in Derry in 1972. The conversation provides valuable insights into Ballagh’s personal experiences and artistic process, shedding light on the political and social context of the time.

The interview provides a unique insight into the historical and cultural significance of the painting.

Critical issues related to the Irish government’s response to the conflict, the impact of the Bloody Sunday event, and the broader social and political implications are highlighted. Ballagh’s commentary on the role of the Irish government, the impact on nationalist communities, and the establishment of the Special Criminal Court adds depth to the discussion.

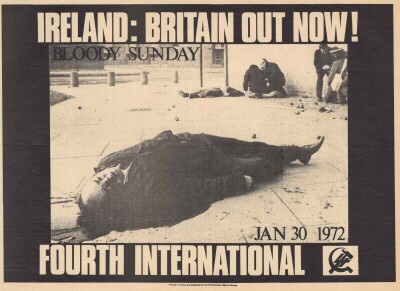

Bloody Sunday Painting – the Thirtieth of January – Robert Ballagh

Thursday, January 20 2022. John Meehan interviews the artist Robert Ballagh in Number Five Arbour Hill.

We are talking about Robert’s painting : The Thirtieth of January, a representation of Bloody Sunday in Derry, January 30 1972.

John Meehan :

Why did you zone in on Derry’s Bloody Sunday , and put so much effort into making this painting? What makes it different from so many other big events during “The Troubles” in the north of Ireland, which lasted for 30 years, from 1968 to 1998?

Robert Ballagh

Well, it’s a long time ago now 50 years, but I have to say that it had an enormous effect on me, and I don’t think I’m alone with that historical experience. I suppose one thing I should say, I was only thinking about this, and I haven’t said anything about this experience to others. I’m a Dubliner. I’ve lived all my life in Dublin. But unlike most Dubliners – it wasn’t by design – I had an extraordinary rich knowledge of the North of Ireland, before the conflict began. Because I was a professional musician in a showband. We used to play at least once or twice a week in the north. So I was in every town village or city in the north that had a ballroom or ballrooms. And so I experienced the reality of life in that society, and became very aware of the sectarian differences, shall we say – the nature of the society, which people didn’t appreciate at all. I tell one very short story to illustrate that. We played fairly regularly in one of the very popular ballrooms in Belfast : Romano’s in Queen Street. We developed quite a following! In the show business vernacular the word groupie was used. These girls used follow us, they came down to Dublin once or twice to hear us. And we were playing one night in Romano’s.

After the dance, they came up and we’re talking to us. They asked “When are you playing again in Belfast?”.

I remember saying “Oh, I think we’re here next week.”

“Oh, really?”

“Yeah – we’re playing in a ballroom called the Astor” which I knew was in Smithfield.

And they said, “Oh, we can’t go there.” And I said, “Why?” – because it was a public ballroom. It wasn’t attached to any organization or anything. It was a public ballroom.

They said, “Oh, no, that’s a taig hall”

And it was the first time I realized, and we realized, that our fan base in Belfast was Protestant.

John Meehan :

What year was that?

Robert Ballagh :

That would have been 1961 or 1962. Romano’s was a public ballroom as well. But obviously the dancers there came from the Protestant side. This was an awakening certainly for me and those of us from from Dublin. This society was very much divided. And I remember a fellow who played the saxophone in the band and his cousin lived on the Falls Road. He used to come and see us quite regularly. And this particular night – I don’t know where we were playing. But he turned up and he was bruised all over and had been savagely beaten. His name was Charlie. I said, Charlie, what happened to you?

He said, I made a big mistake. I went to a film in Belfast there last week, and walked home. And I was walking through the Village, which is a Protestant loyalist sort of area, quite near the Falls Road, actually. And he said, I was feeling very peckish and went in to buy fish and chips. And he said, for whatever reason, they realized that I was a Catholic. They beat the lard out of me. And so all those little stories and experiences conditioned me certainly to appreciate the seismic nature of the society in the north. So, when the Civil Rights campaign began, I was enthusiastically supporting it. I was seeing what was going on, etc. I was shocked in October 1968, when Derry civil rights demonstrators were beaten off the streets by the police, and, that just reminded me of the life on the road. We were coming back to Dublin after a dance somewhere, say in Derry. And we would be passing through the north, quite late at night.

The one thing you dreaded was being stopped by the B Specials. Thankfully, they didn’t do anything too seriously wrong. Like what happened to the Miami showband many years later. But they would harass you and hold you up. It just reinforced this feeling that this society was not working, it wasn’t right, and needed to change. And certainly, in those early days, the Civil Rights Movement seemed to be the way that somehow or other some change would be achieved. So as I say, October 1968 in Derry was a big shock. The next big shock was in the next year, in August 69, when sectarian gangs ran amok through nationalist areas in the Belfast area and other areas across the north. The Battle of the Bogside occurred in Derry – invading loyalist gangs were supported by the State forces. I was really shocked, and challenged by all of this. But funnily enough, I didn’t know what to do about it at all. But I remember that the leading and most prestigious art exhibition way back then was called the Irish Exhibition of Living Art. In 1969, believe it or not, there was no adequate exhibition space in Dublin. And a decision was made to stage the exhibition in Cork, and then have it go up to Belfast afterwards. And we all went down on the train to Cork for the opening, it was a fun occasion. And then to everyone’s surprise, Michael Farrell – the artist – who was living in France at the time, and hadn’t exhibited any kind of political leanings – made a dramatic political decision. He was awarded a first prize which was a cheque for a lot of money in these days – a considerable chunk. Out out of the blue and to everyone’s surprise, announced that he was giving the money, the prize money to the Northern Refugee Fund. This was a fund established to help those who were fleeing the conflict in the north. Farrell withdrew his painting from the exhibition in Belfast. And this caused some thought among the rest of the artists in the exhibition. Eventually, around a dozen artists decided To follow Michael’s example, and withdraw from Belfast. I was one of those artists. I had won second prize of the exhibition with a painting called marchers, which was part of a series of paintings that I did in 1968 and 1969, which were inspired by the Civil Rights campaign in America, and the Civil Rights campaign in the north. So what actually happened was this. Even though there would have been 100 or more artists in the exhibition – with the withdrawal of 10, or so and the accompanying controversy, the exhibition was actually cancelled in Belfast. I wrote a letter to the papers. Michael Farrell and other people did the same. But a problem for me arose very shortly afterwards, when I was invited to show in an exhibition, which was organized by the Arts Councils of Scotland, Wales, Ireland, and Northern Ireland, and was called the Celtic Triangle. And the exhibition was to start in Edinburgh then go to Cardiff, then Dublin, and then Belfast, and I suddenly realized I had to make a choice. Do I continue with this boycott? Or do I try to do something that has something to say about what’s going on? So I chose the latter after some thought. And that was the easy part. The hard part was, what do I do? You know, so I do what I think any sensible artists does. I studied art history and looked at what other artists in the past had done in trying to deal with similar circumstances in their own time. And the one painting that really stood out quite quickly was Goya’s famous painting called the Third of May, where he painted an actual events that happened in Madrid. Because at the time, the French were occupying Spain, and there was an uprising and the French soldiers, executed Spanish people in Madrid. That was the event Goya painted. And it struck me that his image of French soldiers shooting Spanish people on Spanish soil was relevant to Ireland. The British Army had come in, and was threatening Irish people on Irish soil. So it struck me as an image that worked, that I could work with, and try and do something with. And so I did an adaptation of Goya’s painting. Also, because I had to do a few pictures, I did an adaptation of a painting that Jacques Louis David did, called The Rape of the Sabine Women, which was a comment on the violence that broke out after the French Revolution. I did a version of Eugene Delacroix’s Liberty on the Barricades, which again, was commenting on the French Revolution, and the barricades. Contexts seemed to be appropriate, because of course, the nationalist people were throwing up barricades to defend their areas in various parts of the north. So the paintings toured around. And the response was very frustrating for me, because nobody seemed to see that I was trying to make a comment on the conflict….

John Meehan

If I could stop you there – They were admiring the art…..

Robert Ballagh

They weren’t even admiring the art!

John Meehan

I think there’s evidence that they were! If you don’t mind me throwing that in. I’ve come across that behaviour. I only say this as a punter. When I started publicizing your new painting in a small blog, there was a huge reaction to it. It just grabbed people’s attention.

Robert Ballagh

Oh, now Yeah. Yeah.

John Meehan

If you don’t mind me saying, Bobby, that’s true of a lot of your paintings because because they’re brilliantly done.

Robert Ballagh

But if I can go back to then. It took, I would say, certainly five, maybe even 10 years for people to appreciate what I was trying to do. Initially the works were dismissed by critics. Of course, I didn’t know what the public thought. Critics called my work pathetic reworkings of classical paintings that did no service to the originals, etc. And no comment whatsoever on the north or, you know, what was going on or anything like that. And when the paintings eventually arrived in Belfast, I thought at least here somebody will get it, you know. And the friend of mine was actually Exhibitions Officer with the Arts Council. The Arts Council, in those days, had a gallery in Bedford Street in Belfast. It had a shop window, and he put the the Liberty figure on the barricades in the window. And when the exhibition closed, I contacted him and said, you know, was there any response? And he said, No, not really. Oh, yes, we did get one, just one complaint. And I said, Who was that? Oh, a DUP councillor. So I thought at last somebody’s got it. And he said, No, he was objecting to the naked breasts in the picture. So at that, in those days, nobody got it. Maybe Bloody Sunday played a part. Because this was all before Bloody Sunday. But after the actions of the soldiers on Bloody Sunday, etc, that painting of the Third of May – which is known as The Firing Squad, in some circles, people seem to get it. And then I suddenly discovered my painting was being used in many publications dealing with Bloody Sunday, even though it was painted before Bloody Sunday. So that said, I suppose that’s a long way of getting around talking about the 50th anniversary of Bloody Sunday.

John Meehan

I think one of the things this illustrates is that, going back to what you said earlier, there was an awful lot of evidence around, if people were willing to see, that there was something fundamentally wrong with six county state. And your examples of basic sectarianism, let’s call it that. You might at one level say, well, that’s just somebody’s individual bigotry. But I think what you’re saying is : these were symptoms of a general problem in the structure of the state.

Now, part of that was when the Battle of the Bogside occurred in August 1969, it was a significant turning point in the north. The reality was, the level of protest got to such a point that working class people very took over their area. They made it clear : the northern state and its repressive apparatus was not going to trample roughshod over them. The residents of the Bogside fought back. It got to a stage where the outside states – the Westminster British state and the Irish state ruled from Dublin, had to act. The northern repressive apparatus was going to escalate its attack. Would the British or Irish states have to move in and stop? Now, the fact is the Westminster state sent in the British Army. At the start, the weary working class of Derry said, Okay…….this isn’t ideal, but we’ve beaten back the RUC, the loyalist mobs and the B Specials – we have stopped the pogrom. Initially, the relationship between the Derry working class and the British army wasn’t hostile.

Robert Ballagh

That only lasted quite a short time. They weren’t students of constitutional law – even though the British say they haven’t got a constitution. But the army were sent in. And that was the only way they could be sent in to support the police. They took the pressure off the people, initially, they were under law supporting a sectarian police force. So it had to go wrong That’s my judgment.

John Meehan

So you say, for a short time this happened, right. But looking back now events don’t always happen in a pure way. From the point of view of the people in the Bogside, it was their first real victory over the northern repressive state. Since partition.

Robert Ballagh

Oh, yeah. There is no doubt about that.

John Meehan

It’s the first one in 50 years. That’s the way it happened. We had Bloody Sunday in January 1972.

Robert Ballagh

The Stormont apparatus certainly thought that things were spinning out of control from 1969 onwards. The Unionist government decided to lock up every nationalist it could lay its hands on. That’s what happened in 1971. They managed

Firstly – to have a totally one sided policy where the vast bulk of those who were picked up were from the nationalist community.

Secondly, most of those who were picked up had nothing to do with any subversive activity or whatever, because many actual activists seemed to know what was going on and weren’t at home when they arrived.

John Meehan

if you don’t mind me saying it was a bit of a patchwork. Some did, and some didn’t. We have testimony, say, from a lot of publicly known activists like Michael Farrell, and John McGuffin – a number of people like that were interned. And that’s not all. You have the case of the Hooded Men, for example. What I’d like to suggest is that the state did this, because they thought it would work.

Robert Ballagh

It was a disaster. From their point of view, and from everyone’s point of view, and that gave rise to rioting. It gave rise to deaths, it gave rise to constant demonstrations, raids, rallies. And you know what, I introduced this now because a lot of people don’t remember. But the march on Bloody Sunday was a civil rights march, and it was an anti internment march.

John Meehan

There is a smashed placard in the painting.

Robert Ballagh

Yeah. That was put in quite deliberately, to, you know, make people aware that, internment was a still a huge issue, and that this was an anti internment rally or a march and demonstration. And I would say that, without doubt, the British authorities and the northern authorities said, we’ve had enough of this, you know, and plans were put in place.

John Meehan

Getting into the detail of the painting. You have a document there from Robert Ford. And you got that wording from a pamphlet by Eamonn McCann. Ford wrote these words some months beforehand.

Robert Ballagh

I put this in because I believe that this wasn’t some accident. This wasn’t a few squaddies gone berserk or anything. This was a cold calculated plan, and we can go into the nature of that plan. But certainly, I put in this document, this statement in document form, because I wanted people to look at the picture and understand what happened and why it happened. And that Major General Robert Ford, who was one of the officers on duty on the day from the parachute regiment, sometime before said that he had come to the conclusion that the only way to restore law and order was to shoot selected members of the “Derry Young Hooligans”. Well, if that’s not a license to kill, I don’t know what it is.

John Meehan

The Saville Tribunal met in public in Derry and London. It went on for months and months, Eamonn McCann attended every single session. He highlights the important facts. McCann reports that Major General Robert Ford wasn’t an active participant in the assault. He went up to the top of a hill, the man who set up the plan. Ford roared “Go On the Paras” – the title of McCann’s pamphlet. The paratroopers went in, and subsequently murdered 14 demonstrators – that was the result of Ford’s shout from the rooftops.

Robert Ballagh

Interestingly enough, as well. And I saw the clip only recently. Because because the anniversary programs are showing old clips. Robert Ford gave the press briefing immediately after the shooting. And he stated categorically to the world’s press, that the Paras only opened up after they were fired on. And they only discharged four rounds. And that’s his version of events. So I mean, when several concluded that none of the victims were armed. And all of them were innocent. How did the Paris managed to shoot 13 People with four bullets? That’s pretty good, extraordinary achievement.

John Meehan

I don’t know where you were, when it actually happened. I was spending that weekend in the house of Máirín Johnson. The news started to come through. I do remember watching the TV news report. You didn’t have to understand all the nuances. We knew immediately the British Army had opened fire on civil rights demonstrators

Robert Ballagh

The British propaganda machine stepped into action immediately.

John Meehan

Almost nobody in Ireland believed the British version. The next day I was in school. There’s a big aura on the Irish Left about the the term “general strike”. This was the only general strike I’ve personally lived through. Such things, happen. The school shut down. Eventually we realized this was happening all over Ireland. It wasn’t just the pupils. It was the staff, the teachers, everybody. And people were going impromptu on delegations to the British Embassy. It was ceaseless. This event set off a huge mass movement. South of the Border as well as the north. This part of the story is omitted from most narratives – the Irish Times recently ran a small story headed “Days of Rage”! . But the fact is, this was a genuine mass general strike. People went on strike over this incident, they identified the cause was the British state and it ended up with a huge march in Dublin, where the British Embassy was burned to the ground.

Robert Ballagh

Like yourself. I saw the TV news. I was, like everyone else, shocked. But I was also angered. And when I heard that was going to be a march in Dublin, to the embassy, I said, I’m going on that. And as it transpired my wife and my daughter who was three at the time,

John Meehan

This was Rachel.

Robert Ballagh

Yeah. Probably involuntarily! I told her that she was in a pushchair. And the thing I remember was how the anger kind of shifted to a rage, to a desire for some revenge or something, some action – some effective action. And I remember like, as we walk through the city, any premises that even hinted at British ownership or anything, was not safe. And, and I do remember when we passed the British Airways office at the bottom of Grafton Street, the plate glass windows came in, crashed down, and that was the mood. And when we got to the embassy, there was a crowd already there. And there was palpable anger. And at the start, that was just shouting and roaring and the odd brick flying. Slowly, but surely, bottles started flying, and then those bottles changed into bottles with petrol and rags in them. And they were banging off the face of the building. And then eventually, you know, Windows got broken, and then the petrol bombs got inside. And it took quite a while for, you know, the conflagration to begin. But I’d have to say, parental responsibility overtook me. And I said to my wife Betty, I don’t think it’s such a good idea to have a three year old child with a possible riot about to start. So we departed and missed the final conflagration when the embassy went up. But also we thankfully missed a savage baton charge. The guards, at last, seized control of the situation. They were completely pushed aside at the start of the day. And I do remember that a friend of mine – like myself would have been standing looking – he wasn’t an activist or an arsonist! He was standing there, but he stayed. And unfortunately, with the baton charge, he got bashed by the guards.

John Meehan

This was after the building had been burned to the ground.

Robert Ballagh

The embassy was well on fire. So the guards, I presume, see, I wasn’t there, but I presume the crowd thinned out a little and the guards decided they were going to clear the street. And he had head injuries to the extent that he needed 13 stitches. So it was a fairly nasty business. I would see that as the kind of beginnings of the official response to quell and damp down public anger over the existence of the northern state and British occupation. This led fairly quickly to the establishment of the police heavy gang and the Special Criminal Courts.

John Meehan

I was at the front of the crowd, where there was a line of police who were confronted by a line of women, many of them street traders. The women started a dialogue with the police standing in front of the doomed embassy. The women had names of the cops, addressed them on first name terms. The Gardaí were advised they were doing a great job – provided they did not look behind at the fire, or try to put it out. If they looked around, there could be a lot of trouble. So looking straight ahead, everything will be fine. The police realized that it was in their interest to do exactly what the women told them. There was a mixture of fear and grudging sympathy among the boys in blue.

Robert Ballagh

Oh, yeah, I would think so, with what was going on. And then the word filtered back.

Orders came down from above – Let’s get stuck in.

John Meehan

Word filtered back through the crowd. An organized group realized: “we can burn down this embassy” – the police are not in any position to stop us, although they have the material means. They don’t have the social support to do it. The bottles flew over. And the women resumed banter with the cops saying, “Look, if you don’t turn around, you didn’t see anything, did you?”. Petrol bombs were flying overhead. The cops were told they would get good overtime money. At this stage, they were starting to join in and laugh. Big asbestos screens, designed to stop the anticipated attack, were preventing the fire from spreading – the attack might not succeed. So a couple of people went past the police and tore big holes in the barriers, and poured petrol in. The working class of Dublin effectively took control of the situation, and worked out the best way to burn down the British Embassy.

Robert Ballagh

From above, the view was that this could potentially be very dangerous. Let’s stamp it out as fast as we can. So some in authority thought, naively, I think, that the crowd might turn around and start moving towards Leinster House or some other crucial locations. I think that was hardly likely. But I believe some parts of the establishment thought this was a possibility.

John Meehan

It’s worth looking at those events from the point of view of people who are interested in getting the partition settlement destroyed, because that’s a legitimate objective. Can we learn from that for the future? We can’t do anything about the past. The reaction of the southern state to these events, lagged way behind what was necessary. Only a fool would think that just because there’s a peace process now, that similar events couldn’t happen in the future. The question really is if large working class communities are assaulted by the state, and it gets to a stage where there’s an open confrontation – what social forces control the territory? What’s to be the role of people outside? And what’s the role of the southern state to be in the future? That’s really the crucial question, it seems to me. We can think such conflicts won’t happen. I think that’s crazy. Given what we know about what happened in the past, it’s just crazy. And if it does happen, and you think it’s going to happen, you need to have a policy for what to do in that situation.

Robert Ballagh

Well, I think that if we look at history, I think the actions of the southern state in a crisis dealt a severe lesson for Northern nationalists, going back to August 69. The events around the sectarian attacks on the nationalist communities led to the decision by the Westminister government to send troops in. And as Jim Callaghan ruefully said at the time – he was the British Home Secretary – it was easy to get them in and won’t be so easy to get them out. That was obviously the case. But also, the Irish government, sadly, was caught totally unawares. It didn’t know what to do. It started all sorts of things like setting up field hospitals along the border and refugee camps and things, and set up a relief fund, which is quite interesting.

It’s worth looking at those events from the point of view of people who are interested in getting the partition settlement destroyed, because that’s a legitimate objective. Can we learn from that for the future? We can’t do anything about the past. The reaction of the southern state to these events, lagged way behind what was necessary. Only a fool would think that just because there’s a peace process now, that similar events couldn’t happen in the future. The question really is if large working class communities are assaulted by the state, and it gets to a stage where there’s an open confrontation – what social forces control the territory? What’s to be the role of people outside? And what’s the role of the southern state to be in the future? That’s really the crucial question, it seems to me. We can think such conflict won’t happen. I think that’s crazy. Given what we know about what happened in the past, it’s just crazy. And if it does happen, and you think it’s going to happen, you need to have a policy for what to do in that situation.

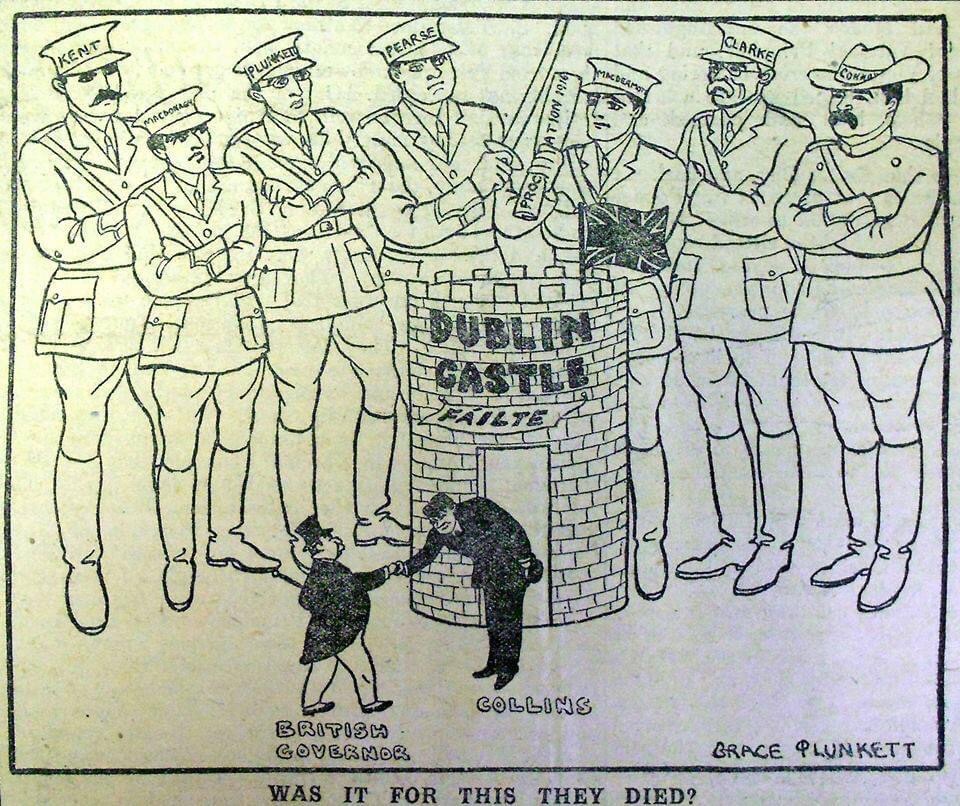

The conflict lasted for 30 years or more. This was a consequence of history. Once the Northern State was was set up, and the Boundary Commission did nothing to ameliorate the consequences of that decision, the Irish state effectively turned its back on the north and allowed a six county sectarian state to develop. For 50 odd years that state discriminated against one section of the population. In 1969 the Irish government literally had no contacts – had no understanding of what was going on on the ground. In fact, I remember reading somewhere that those days in the north of the island saw the greatest movement of civilians since the Second World War in Europe. The cabinet then decided to set up a relief fund to make monies available for defence committees that had been set up in various parts of the north. Also – and I think significantly – and this is still an issue of contention. I believe the cabinet established a covert plan to import arms, which were not for the Irish army, but were to be distributed to the few contacts that they’ve made with defence committees. But only in the context of a repeat of August the 15th. Quite quickly, that plan was rumbled because it seems it was ill conceived. The response within the cabinet was for taoiseach Jack Lynch and his supporters to deny any knowledge of this covert plan. The Lynch faction scapegoated colleagues : Finance Minister Charles J Haughey and Agriculture Minister Neil Blaney, who were immediately dismissed from their cabinet positions. Kevin Boland, who was also a government minister, resigned in solidarity with the guys who have been dismissed. A mistake is often made by people looking at it now, who believe Boland was sacked at the time. He wasn’t – only only two ministers were sacked. This eventually led to two arms trials. Both Haughey and Blaney were acquitted. So were the other defendants : Albert Luykx a Belgian arms dealer; John Kelly, a Republican from from Belfast, and Captain James Kelly : the army officer who got the job of trying to run this covert arms importation plan. My reading of the events was Captain Kelly was obeying orders as an Army officer. The end result of all of this was a further distancing of the Irish Irish state from what was developing in the north. More significantly, it led to a widespread feeling amongst many northern nationalists that whatever was going to happen, they were on their own. They weren’t going to get any significant or meaningful help from the Irish state. And I think we can draw from that : this provided the opportunity and the conditions for the rise of the Provisional IRA. As a consequence of that the conflict lasted 30 odd years.

John Meehan

If I could just add to that : the overall solution is only going to come from a mass movement that has support north and south. So the question is, what role is the Southern state going to play? You just described perfectly what the state did in the 1969-70 period. It was trying to ride two horses at once. One horse was the historic imperative to end partition. That aim was written into the constitution of 1937. The other horse was to operate partition. The capitalists running the six county state were the targets of an enormous assault.

Robert Ballagh

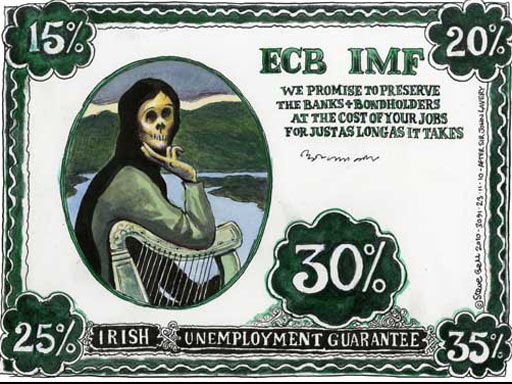

The nationalist working class in the north were a risen people, and then it spilled over into the south. After Bloody Sunday the southern state established the non-jury Special Criminal Court, a sentencing tribunal. They got rid of juries, because juries were not going to deliver verdicts that the ruling class wanted. We saw the birth of the heavy gang – a gang of thugs in the police which beat the living daylights out of suspects. Activists in later years – up to and including the present day – have suffered the consequences. These events gave rise to a culture within the guards where, for instance, a few years ago, a million false fines were handed out! This leads us to the conclusion that there is an innate corrupt element within the Irish police force.

Several Garda commissioners have been forced to leave office “under a cloud” – let’s put it this way! It’s like you plant a tree, it grows these roots. Even some police can see this : if you give dominance to gangsters and thugs in a police forces, their methods are going to triumph. It leads to very bad police work if you’re looking for proper forensic investigation. Forensic evidence that would be required in the normal courts was no longer required for the Special Criminal Courts. The guards in my book became lazy; became dependent on confessions, dependent on methods of working that essentially, led to corruption.

I think these issues need to be related to the prospect of an end to partition. And it’s not a case of, well, when we get rid of the border, all of this will be solved. It’s a case of addressing them now. Because the past sometimes catches up with these people. Because of the pressure on criminal courts. These are just the rules of the game : every year, annually, it has to be renewed by the Dáil. At the end of July every year, if they don’t renews, the Special Criminal Court goes. Of course, the establishment now uses the special criminal courts to deal, on a day to day basis, with criminal activities. So it doesn’t have the same camouflage of political action anymore. This is an easier thing to sell, I think, to the public – You want to get rid of the Special Criminal Court, but we’re using it to track down the criminals! And but of course, this is a camouflage just absolutely a camouflage. You see political people are being blackmailed here, and they should reject this blackmail. The fact is that a criminal has as much right to a fair trial as anybody else. That means a jury trial. It’s much better.

I think these issues need to be related to the prospect of an end to partition. And it’s not a case of, well, when we get rid of the border, all of this will be solved. It’s a case of addressing them now. Because the past sometimes catches up with these people. Because of the pressure on criminal courts. These are just the rules of the game : every year, annually, it has to be renewed by the Dáil. At the end of July every year, if they don’t renews, the Special Criminal Court goes. Of course, the establishment now uses the special criminal courts to deal, on a day to day basis, with criminal activities. So it doesn’t have the same camouflage of political action anymore. This is an easier thing to sell, I think, to the to the public – You want to get rid of the Special Criminal Court, but we’re using it to track down the criminals! And but of course, this is a camouflage just absolutely a camouflage. You see political people are being blackmailed here, and they should reject this blackmail. The fact is that a criminal has as much right to a fair trial as anybody else. That means a jury trial. It’s much better.

If you think about that, a jury sits back looks at all the evidence and says, you’ve got to prove this. Because otherwise you’re handing all the power to the judges and the police. Yeah. And the evidence, frankly, is quite strong, that there are corrupt relationships between the criminals and the state. It’s very strong. And if it is already present, the dirt will emerge. There’s no doubt about it. And so this is just blackmail. And unfortunately – I have to say this – the fact is Sinn Féin have changed their policy on the Special Criminal Court. And it’s a lethal mistake, because the state will use this. There’s no doubt about that in the future. Anyway, if there’s a political problem, they will use it to go after political people.

John Meehan

Let’s quickly review the Jobstown Trial of 2017 (Link : https://www.thejournal.ie/courts-jobstown-jury-3469624-Jun2017/) which was heard by a jury. Modern technology was a problem for the police. Recordings played in front of the jury, and the jury could see where the police statements diverged from the recorded visual and spoken evidence. A politician, Joan Burton, who was a government minister at the time, made statements contradicted by the recorded evidence. The defendants were declared not guilty because the jury was able to review all the evidence objectively. But, the police who gave evidence which contradicted the recorded evidence are still there.

Robert Ballagh

Oh, yeah. Politicians are still there. And that’s the problem. Ask yourself : if that had gone before a Special Criminal Court, what would have happened? Would we have seen the same verdict ? And if we look more recently – people who are younger than us two probably were shocked when they saw the documentary on television about the Sallins mail train robbery, when the evidence was overwhelming, that the people charged were innocent. Judges, right up to the Supreme Court even refuted the charge that one of the judges was ill and had fallen asleep. And the man died! I mean, just ridiculous. Yeah. So in other words, what I’m trying to say here is that this is a state we need to attack. And it’s institutions and stuff. And that’s part of the job of getting rid of partition. Actually – I’ve always argued that – in the context of moving towards whatever happens to partition on this island – one thing it cannot be is an extension of this 26 County state.

And if we look more recently – people who are younger than us two probably were shocked when they saw the documentary on television about the Sallins mail train robbery, when the evidence was overwhelming, that the people charged were innocent. Judges, right up to the Supreme Court even refuted the charge that one of the judges was ill and had fallen asleep. And the man died! I mean, just ridiculous. Yeah. So in other words, what I’m trying to say here is that this is a state we need to attack. And it’s institutions and stuff. And that’s part of the job of getting rid of partition. Actually – I’ve always argued that – in the context of moving towards whatever happens to partition on this island – one thing it cannot be is an extension of this 26 County state.

We must have a debate on a new constitution. Ther are things that, in spite of all the rhetoric about a united Ireland and how wonderful it might be and blah, blah, no work is effectively being done on an official level. Let’s discuss these things. Not just what kind of a new Ireland do we want, but what do we definitely not import from this state into a new Ireland and vice versa. But what strikes me is the capitalist classes are ahead of us. It gets down to the dirty nitty gritty.

John Meehan

You mentioned the Miami showband massacre in your interview.

A proper investigation of that case is required. A high ranking northern police officer by the name of Drew Harris rose to the position of assistant commissioner of the Northern police. He actively blocked investigations of the Miami Showband massacre. So we’re witnessing a 32 County integration of the state apparatus, a fusion if you like. Well, is that such a surprise? Bríd Smith, the Dublin South Central TD, is one of the few politicians who has raised this issue. We require an urgent campaign to sack Harris.

Robert Ballagh

If you look at what the Miami showband survivors are saying : they were absolutely disgusted with Harris’s appointment – he is presently the boss of the Gardaí, the Commissioner – and his reappointment. I was shocked, shall we say, by that appointment? For 101 reasons – because of being reasonably familiar with what went on in the north over the last 30 years or so, and Drew Harris’s close involvement with the collusion process? The architecture of collusion, shall we say? Establishment TDs are thinking this is a wonderful idea, and we must forget the past. But if any people in Sinn Féin, for instance, proposed anything, they’re attacked with denunciations about the past!

It’s just a total contradiction in terms of dealing with the issues. You notice the trade union campaign for Irish Unity and Independence – very good. That’s an extremely important and positive objective. Organizations like that have to take up those kinds of issues They should not only be saying to people – it’s the capitalist politicians trick – vote for us!

We can’t do anything at the moment because we have this rotten government, vote for us. And then things will change.

Well, I’m sorry. We can’t operate like that. Look at the ultimately successful campaign to get rid of the abortion ban from the 26 County state constitution. You’ve got to take the issues up on the ground and continuously campaign and put political pressure on and reject all this stuff. But those who have a very strong vested interest in the economics of the situation are paying close attention to it. And you’ve got the Confederation of Irish Industry and the British equivalent in the north, they’re all studying this very carefully and making plans for possible outcomes, and everything. You can be sure that what they’re planning won’t be in the interests of ordinary workers or ordinary people. So it’s absolutely essential that the ordinary people have to start working on this and making plans for how this is going to play out in the next decade.

Let’s highlight, even today, the role of two significant military officers. That’s Major General Robert Ford, and General Mike Jackson. These people need to be prosecuted. And of course, that’s the point. Right? And that’s why, you know, I mean, on one level, I think it was very important that Savile in his inquiry, found that all the people who were charged were innocent. And it took an awful long time. But that was significant. And I think the families involved were very pleased to have that acceptance. British Premier Cameron’s apology : people were happy with that. But the glaring omission from all of this was who was guilty. I mean, we ended up with the farce of only one soldier being charged soldier F. And, you know, if there’s one thing about soldiers that I know is soldiers follow orders. Soldiers don’t go off on a mad skite on their own. Soldiers obey orders. Who gave the orders? And I mean, in my painting, I hinted at this by including a statement by Robert Ford, who was on duty with the paratrooper regiment on the day, where he very clearly states that he has come to the conclusion that the only way to restore law and order is to shoot young Derry hooligans, as he called them. Well, that’s what they did. Their soldiers were obeying orders. So now I’ve upped the view, which is just a view. I’ve no evidence, but I believe the orders for what happened on Bloody Sunday went right to the top. I believe a decision was made, probably in Downing Street, that this nonsense of street protests has to stop, we need to go in and hit them hard and heavy. And I think they believed that there would be two outcomes now that this is our supposition. But it’s my supposition that, that the British establishment at the very highest level said, we’ve had enough of this nonsense now – civil rights, marches, all this kind of stuff – we’ll go in hard. And we’ll put an end to that, which they successfully did. And the other thing I think they calculated that this will lead to a rise in activities by the provisional IRA, but we will snuff that out in a couple of years. They discovered they were up against a far more formidable foe.

John Meehan

We can’t do anything about the past. But we saw – and you explained it very well – a contradiction between the official policy of the Irish state and the covert arms importation. The reality is that any sensible policy on this issue would say that we have a peace process now on their rules. Okay. Maybe people will play according to the rules, and maybe they won’t. And the rules are supposed to be that you have a referendum, it wins and then end partition. Now, the fact is that the football managers, if you like, who designed this, or especially Fianna Fáil, Fine Gael, Leo Varadkar, have looked at this and said : Focus! This is the wrong game, we’re going to lose it. So they’re now talking about : we can’t have just a 50% plus one, whatever.

Robert Ballagh

Well, I’m sorry, you know, that’s the game they set up. And if they want to change, it – they would need to change the constitution of the 26 county state again. Because that’s what’s actually written down. There’s nothing in it about wait till you get 60 or 70 per cent.

John Meehan :

Brexit was passed in Britain, but in the six counties, it was defeated by 55 to 45 per cent. And we’re still seeing the consequences of that : an erosion of the Unionist electoral position.

Robert Ballagh :

There’s no question or doubt about that. And actually, that is a strange one for left wing opponents of The EU. It has taken the EU, and an attempt to break the EU from the right, to prise away a large section of former unionist voters. So, and it’s this friction now between the British ruling class on the one hand, the Gombeens in the 26 counties on the other. Overlooking them, the French and the German capitalist class are saying : Well, you created this problem. And there’s a big conflict : there is suddenly a prospect which wasn’t there before. It is a strange hybrid one : non Brexit, United Ireland might be on the horizon. In other words, a united Ireland that has some relationship with the EU. I think we’ve got to a stage here, for those of us on the left, who are opposed to the European Union : We have seen that, while we’re opposed to the EU, we’re not in favor of working with right wing opponents of the EU who will make the situation worse.

And I mean, I’ve opposed the EU at every stage, campaigned against every Lisbon Treaty Maastricht treaty etc. But I recognize that the way to deal with this, and to oppose this is not by leaving, because you just become an isolated entity on the outside of this big thing. And with no input into it whatsoever. The way forward, I see is for us, you know, to be critical members of this organization, and seek alliances with fellow critical members within that. I went to Denmark to campaign for the people’s movement in Denmark. I mean, if everyone thinks that everything in the garden is rosy in Europe, they’re deluded. In every country in Europe, there are European skeptics who are being skeptical about it from a progressive point of view. And I mean, that was really brought to light when they tried to introduce a constitution for a new Europe, and it was rejected by the French people. It was also rejected by the voters in the 26 County bit of Ireland. But the point of issue is that there’s no point in just walking away, because that doesn’t achieve anything. The way to move forward is for us to elect decent people to go to Europe. And secondly, for our attitude to change and to become very critical of the things that are wrong with Europe.

Related

Written by tomasoflatharta

May 28, 2024 at 8:50 am

Posted in 2018 Referendum to Repeal the 8th Amendment to the Irish Constitution, 26 County State (Ireland), Abortion, Archbishop John Charles McQuaid, Arts and Culture, “A Carnival of Reaction” - James Connolly’s Warning About the Partition of Ireland, Bloody Sunday, Bloody Sunday, Derry, January 30 1972, Britain, British Empire, British State (aka UK), British State Collusion with Loyalist Murder Gangs, British Tory Party, Catholic Church, Child Abuse, Derry, Derry Civil Rights March, October 5 1968, Drew Harris, Garda Commissioner, Drew Harris, Roya; Ulster Constabulary and An Gárda Síochána, Dublin Governments, Feminism, Fourth International, Garda Síochána, Good Friday Agreement 1998, History of Ireland, International Political Analysis, Ireland, Legislation in Ireland to Legalise Abortion, Mass Action, Miami Showband Massacre, 1975, Paul Murphy TD Dublin South-West, Police Forces in Ireland, Referendum in 1998, Deletion of Articles 2 and 3 from the Irish Constitution, Referendums, Religions, Revolutionary History, RISE, Robert Ballagh, Artist,Political Activist, Robert Ballagh’s Painting, January the Thirtieth, RUC/PSNI, Six County State, Special Criminal Court, Ireland, Unionism, Vatiban, War and an Irish Town (Eamonn McCann)

Tagged with Abortion, Archbishop John Charles McQuaid, Belfast, brexit, campaign, capitalist, consequence, constitution, counties, criminal court, criminal courts, eu, europe, Feminism, Fianna Fáil, Fine Gael, general, government, history, Human Rights, Internment, Ireland, irish, Irish Left, irish-identity, irish-politics, jury, north, Northern Ireland, open-borders, partition, people, police, politics, Racism, significant, Sinn Féin, socialist renewal, state

Leave a comment