Fish and chips? Pesce e pattatine fritte! – Italian Immigration to Ireland in the 19th and 20th Century

Link : Chippers in Ireland – Ralf Sotscheck, Taz

This story originally appeared in a German daily paper published in Berlin, die tageszeitung, on May 10 2025.

Deep-fried fish with chips, vinegar and salt is a favourite dish in Ireland. But it was the Italians who spread the dish there.

Almost all the tables are taken on this Saturday evening in Romano Morelli’s restaurant. The Italian restaurant on Dublin’s Capel Street is narrow but long. Hardly anything reminds you that Morelli’s family sold fish and chips here for over 40 years, when the store was still a chipper.

That’s the name of the snack bars that serve the Irish favourite, fish and chips. A dish that most people would probably not associate with Italy, although Italian immigration to Ireland in the 19th and 20th centuries had a significant influence on it.

Morelli’s grandfather was one of the last fish and chip vendors to come to Ireland with the first wave of immigration from Italy. He bought the store in 1948, which at the time was a snack bar with slot machines in the basement, says Romano Morelli. To this day, the chippers look almost identical: They are usually a bare room divided into two halves by display cabinets and deep fryers.

On one side, customers wait for the greasy goods, while the other side frantically prepares them. Italian is often spoken in these stores. Above their entrance doors hang the owners’ nameplates: Macari, Borza, Coffola, Fusco, De Vito, Cassoni, Caprani.

Almost all of these families or their ancestors come from Casalattico, a municipality in the central Italian province of Frosinone. More than 2,400 people whose families originally come from this village live in Ireland. Even today, the 800 or so inhabitants of Casalattico celebrate these ties every year and hold a festival on St. Patrick’s Day, the Irish national holiday, on March 17, with music, dancing, Irish flags and fish and chips (and, of course, vinegar and salt).

The connection between the community and Ireland is said to have started with Giuseppe Cervi in 1885, who accidentally left the ship he was on to the USA in Ireland. He hired himself out as a labourer in Dublin until he had earned enough money to buy a coal stove and a handcart with which he sold fish and chips outside the pubs. The business idea came from the north of England, where the meal was sold outside the factory gates.

Breen Reynolds, a former geography lecturer at Trinity College Dublin, doubts that this part of the story really happened in an interview on Irish television. However, it is confirmed that Cervi soon had enough money to rent a store. He ran it with his wife Palma, who is said to be the origin of the expression “one and one”, which is still used in Dublin today to order food. She always pointed to the menu and asked: “Uno di questo, uno di quello?”, meaning “one of this and one of that”.

The customer just had to nod.

Word of the Cervis’ success soon spread at home and many followed them to Ireland. By 1909, there were 20 fish and chip stores in Dublin run by Italians. However, the wave of immigration ended before the First World War.

“My grandfather on my father’s side was the exception,” says Romano Morelli, a short, slim 73-year-old. “He only came to Dublin from Casalattico in 1916, he was 16 years old and hardly spoke any English.” But he soon left Ireland again and went to England. “He thought the Irish were crazy because there were always shootings in Dublin city center,” says Morelli. His grandfather did not know that he had been caught up in the Easter Rising, which heralded the end of English rule in Ireland.

Morelli, who has pushed his glasses over his cap, speaks with a Dublin accent; he was born in the city. As a teenager, he spoke fluent Italian, but it has since become a little rusty. His three children speak the language better than he does because they often visit the homeland of their ancestors. The family still owns a house in Casalattico; Morelli was last there in 2018 for his daughter’s wedding.

“My grandfather bought shares in a snack bar in Kent,” says Morelli. “He later obtained British citizenship.” But then came the Second World War and the British interned all Italians, even if they had English passports. They were sent to a prison camp on the Isle of Man. After a few weeks, many of them were transferred to a ship that was supposed to take them to Canada.

“My grandfather wasn’t there, he remained in captivity in England until the end of the war, and that was his good fortune,” says Morelli. “The ship was sunk by a German torpedo.” After the war, his grandfather was released and instead of returning to England, he went back to Dublin and bought the store.

Boom in chip shops in Ireland

Morelli’s maternal grandfather had worked in a snack bar in Portrush in Northern Ireland until the Second World War; this part of the family had immigrated from Casalattico at the beginning of the 20th century. Then someone warned him to pack up everything and flee with his family across the border to the neutral Republic of Ireland, because the British army was also arresting all Germans and Italians in Northern Ireland. “So he ended up in Bray, south of Dublin, and got a job in his cousin’s chippy,” says Morelli.

The Second World War was followed by another wave of migration. Casalattico was located on the Gustav Line, which ran right through Italy and to which the German Wehrmacht had retreated after the Allies landed in southern Italy in September 1943. “The inhabitants hid in the woods,” says Breen Reynolds. “When they finally returned to their village, their livestock was dead and the land was ruined, they had to leave, they had no other choice.”

Connection between the emigrants and Italy remained

They went to live with their relatives in Ireland. However, the connections between the new immigrants and their old homeland remained. One of the emigrants was even elected mayor of Casalattico in 1955, even though he had long been living in Ireland.

The influx led to a boom in chip shops throughout Ireland from the late 1940s. The Italians were warmly welcomed. “It was a backbreaking job with long hours,” says Reynolds. As with a subsistence farm, every member of the family had to help out. As a result, the Italian families mostly kept to themselves. The “Club Italiano Irlanda” has existed in south Dublin since 1987, organizing cultural and social activities for the Italian community.

“My parents worked here until they retired in 1980 and left the store to me,” says Morelli. “At the end of the 1980s, I converted it into an Italian restaurant.” The decision back then was unusual. Most Irish people didn’t have the money to eat out at the end of the 1980s and there were only a few Italian restaurants. But Morelli is satisfied: “The risk paid off.”

Translated with http://www.DeepL.com/Translator (free version)

A note on the Irish Emigration and Immigration Experience

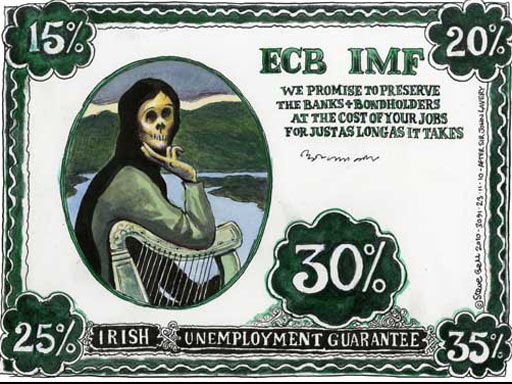

Ireland, between the 1840’s and the 1990’s was a world champion in one activity : emigration, exporting its own people. A Department of Foreign Affairs memo gives us a very good summary of the relevant facts :

Irish Emigration Patterns and Citizens Abroad

Historically Ireland has occupied an unusual place in the wider pattern of European emigration, with very large numbers of emigrants relative to the total population of the country. There was a continuous decline in population from 8.2 million people in 1841 to 4.2 million in 1961. The peak years of emigrant outflow were in the immediate aftermath of the Great Famine of 1847-51. In the decades up to 1921 the vast majority (>80%) of emigrants from Ireland went to America. Post-1921 due to political and economic changes there was shift to Britain which into the 1960s remained the

destination of choice for over 80% of emigrants1, and remained the destination for the largest number of Irish emigrants up until the 1990s.2 Irish emigration is also notable for the number of women who have emigrated – up until the 1980s women’s rates of emigration were often higher than men’s.

Link :

A 1972 RTÉ Programme :

Link :

“The Biggest Foreign Community in this Country” RTÉ 1972

Leave a comment