An Immigrant History of a Dublin Street – Reflections: Dublin’s racist mobs smashed the city centre, 23.11.23

From O’Connell Bridge to the Gate Theatre, via Jamaica, Finland, Ukraine and France – Maurice J Casey

Introduction :

Maurice Casey’s article is brilliant.

This article should encourage all Irish revolutionary socialist activists who are anti-racists to examine our connections with the Eastern part of the European continent.

Below Maurice’s article we publish the words of Imelda May’s stunning poem “You Don’t Get to be Racist and Irish”.

An Immigrant History of a Dublin Street – From O’Connell Bridge to the Gate Theatre, via Jamaica, Finland, Ukraine and France

My thoughts are with all those impacted by the attack that took place in Parnell Square, Dublin, on 23 November. You can find some fundraisers to help here.

Irish migration history is traditionally told as a history of emigration outwards. We rarely talk about the history of immigration inwards to Ireland.

Yet a migrant population has existed in Ireland throughout its modern history. And this community’s overlooked story reflects common European migrant experiences: adversity, cultural influence, assimilation, xenophobia, and so on.

In other words, it is the kind of history that defies notions of Irish exceptionalism.

To explain more, let me take you through the immigration history of a single patch of Dublin city centre. Together, we can traverse the same streets associated with the appalling images from last Thursday; from O’Connell Bridge up towards the Gate Theatre.

I’ll try and give those images of the far-right instigated riots, now burned into so many of our anxious minds, a few historical counterpoints.

A view of O’Connell Bridge, c. 1928.

Let’s begin on O’Connell Bridge and head northwards. As we make our way beyond the Daniel O’Connell statue, we may encounter a Jamaican poet walking against us – if we were taking this stroll sometime in the late 1930s or early 1940s.

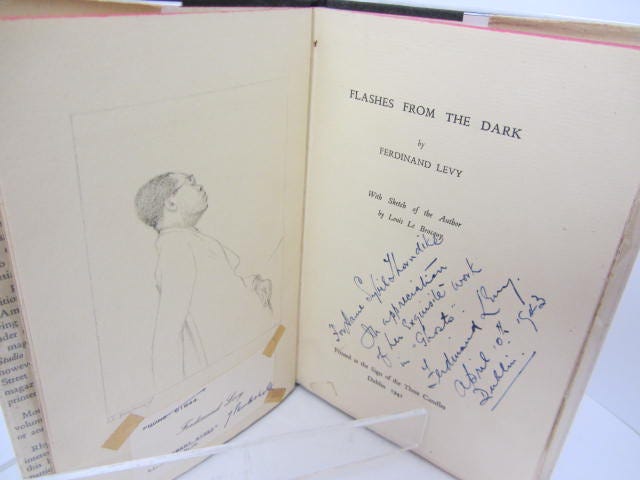

Ferdinand Levy, a Harlem Renaissance poet whose life in Ireland has recently been uncovered by Karl O’Hanlon, lived in Dublin for several years in the 1930s and 1940s.

Levy was a medical student at Trinity College at the time. O’Hanlon notes that his 1941 collection Flashes from the Dark was probably the first book of poems by a Black author published in Ireland. One of his poems recites a flirtatious moment, as he catches the eye of an Irish woman on one of his walks through Dublin’s city centre:

The smile she smiled

Was indiscreet –

Lord, Lord! –

Down O’Connell Street

A signed edition of Flashes from the Dark, with a sketch of Levy by Louis le Brocquy – once for sale from Ulysses Rare Books.

As we walk by Easons and Penneys, we are about to stumble upon another site of African diaspora culture in early twentieth century Ireland. Down the alleyway on our left, Prince’s Street North, you could once find La Scala Theatre, which later became known as the Capitol Cinema.

At this location in October 1921, members of the early jazz group the Southern Syncopated Orchestra performed after surviving the sinking of the boat carrying them over from Scotland.

These visitors received enthusiastic audiences. A couple of years later, however, Black musicians set to become a more permanent fixture in Dublin realised a century ago that Ireland’s ‘thousand welcomes’ are always conditional.

In September 1923, La Scala Theatre was the subject of a protest from the Irish National Association of Musicians when the theatre advertised a new Dublin-based jazz group known as La Scala Rhythm Kings. The Irish musicians’ organisation objected to the performances in racist terms, stating that ‘on moral grounds the admission to Ireland of coloured musicians is undesirable’.

Now we reach the GPO, the post office dearest to the hearts of Irish patriots. This building was, during the events of Easter week 1916, occupied by Irish revolutionaries — and two foreign sailors, one from Finland and the other from Sweden.

The story was recalled by Liam Tannam, one of the Irish volunteers in the GPO in 1916:

I went to the window and I saw two obviously foreign men. Judging by the appearance of their faces I took them to be seamen. I asked what they wanted. The smaller of the two spoke. He said: “I am from Sweden, my friend from Finland. We want to fight. May we come in?” I asked him why a Swede and Finn would want to fight against the British. I asked him how he had arrived.He said he had come in on a ship, they were part of a crew, that his friend, the Finn, had no English and that he would explain: “Finland, a small country, Russia eat her up. Sweden, another small country, Russia eat her up too. Russia with the British, therefore, we against.”

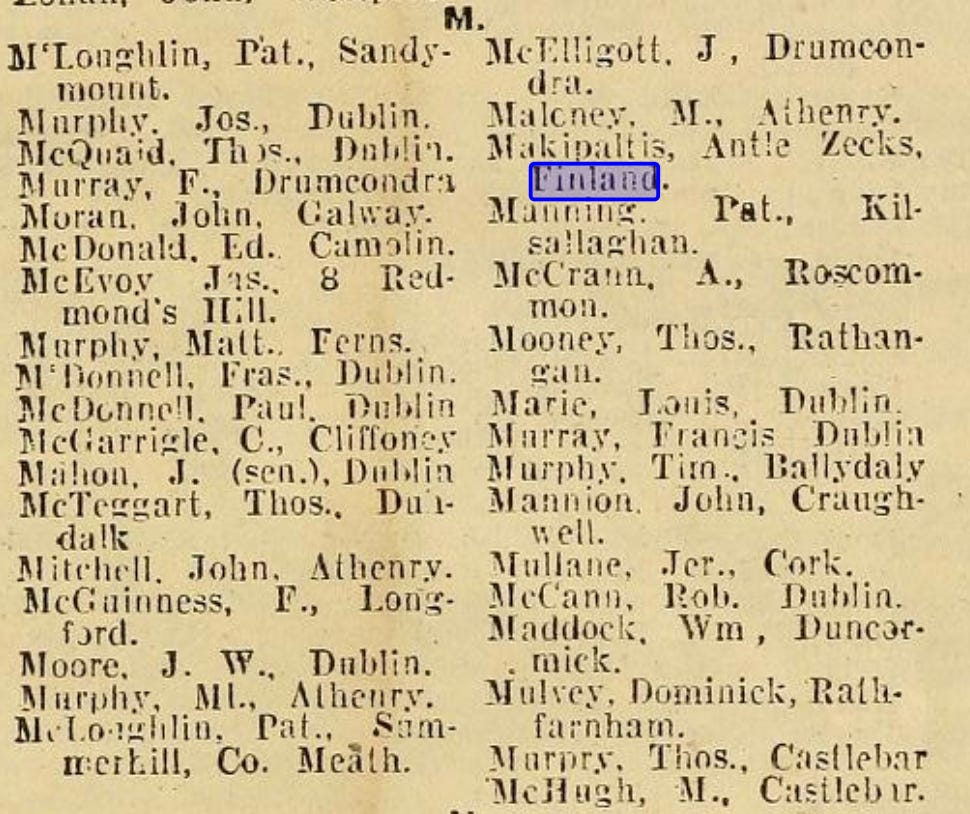

Although little more is known of the Swedish sailor, the Finnish Rising participant was, as historian Anthony Newby has traced, a man named Antti Makipaltio, who was rounded up by British authorities and imprisoned in Kilmainham Gaol for a number of weeks. Here, one Irish comrade recalled the Finn ‘Tony’ learning to say the Rosary in Irish. Later, Makipaltio emigrated to the United States where he spent the rest of his days.

Antti Makipaltio providing the only mention of ‘Finland’ on the list of those arrested after the Easter Rising

Of course, the story of the Finn and the Swede in the GPO is largely a tale of spontaneous migrant solidarity with the Irish revolution. For the story of a more sustained case of solidarity from a former citizen of the Russian Empire, see my article on Latvian socialists in revolutionary Dublin.

If you (understandably) would rather not read an 8,000+ word academic article, I spoke about the research on a recent episode of the Irish History Podcast:

Up ahead of us, the statue of Charles Stewart Parnell looks down O’Connell Street.

In June 1890, Parnell attended the London wedding of a close comrade in the Irish nationalist cause, William O’Brien. The bride was Sophie Raffalovich, daughter of a Ukraine Jewish family who left behind their native Odesa and moved to Paris, where Sophie was raised.

Devoted to her husband and his cause, Sophie funnelled part of her family wealth into O’Brien’s political career. Sophie’s younger brother Marc André Raffalovich also befriended Irish nationalists through her sister. He hosted a salon in London, frequented both by Irish Parliamentary Party politicians and the world of queer aesthetes of which Marc André was a part.

There is an irony here: Marc André Raffalovich was the author of an early French-language defence of homosexuality, published around six years after his sister married into the Irish nationalist elite. His brother-in-law William O’Brien, meanwhile, had been one of the instigators of an early ‘homosexual scandal’ in Irish politics: the Dublin Castle affair of 1884.

Sophie Raffalovich’s support for her husband became the target of Irish antisemites — an early example of weaponised racism within Irish politics. Patrick Maume notes that O’Brien was heckled at public meetings with antisemitic cries singling out the ‘Russian Jewess’ to whom he was married.

A young Sophie Raffalovich

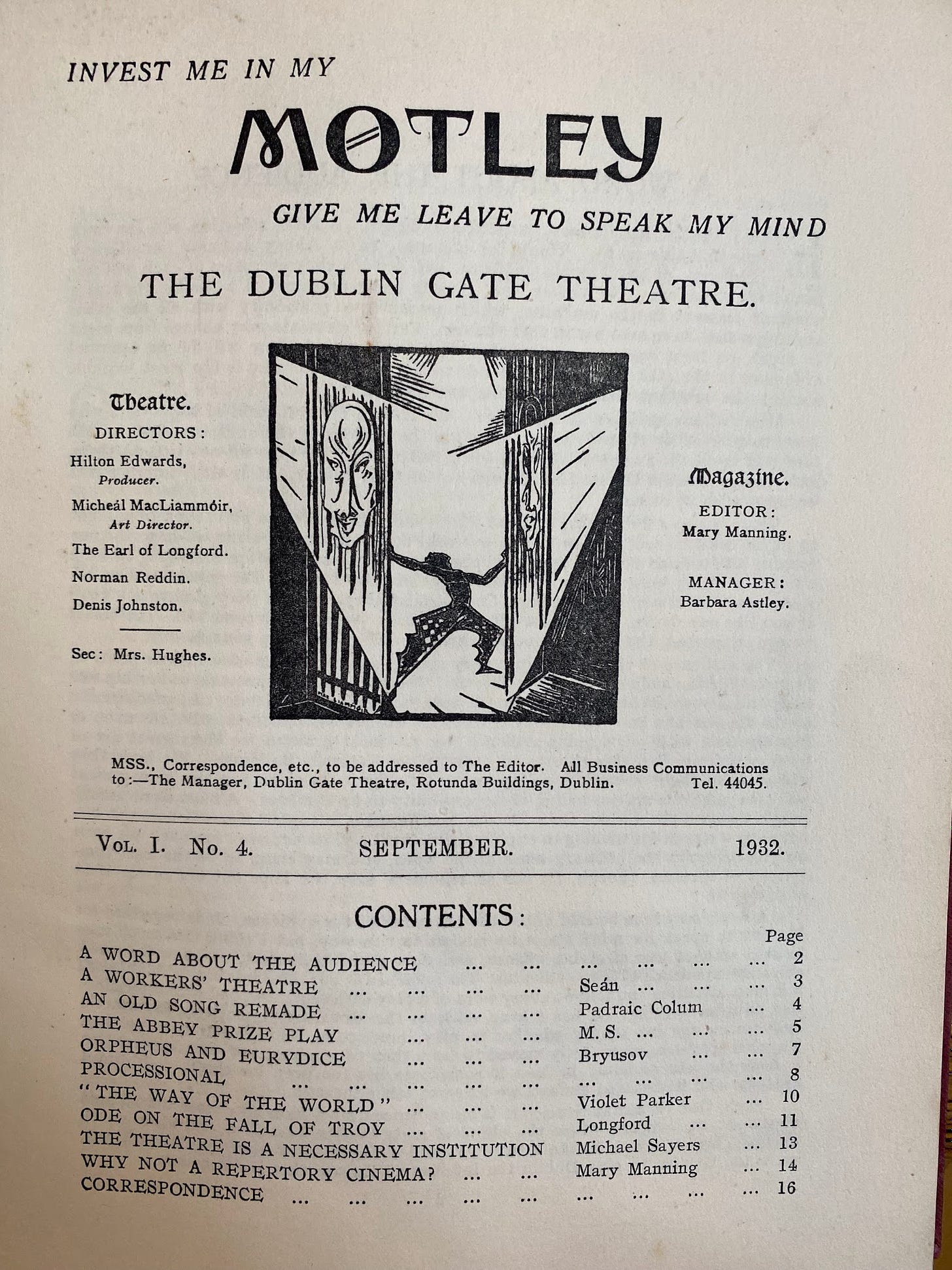

Moving beyond the statue of Parnell, the Gate Theatre appears on our left. Of course, many know about Michael Mac Liammoir and Hilton Edwards, the English-born theatre impresario couple who founded the Gate. But less well-known is the story of the French woman who played an important role in helping them create this Dublin theatre landmark.

Desiree ‘Toto’ Bannard Cogley, a dynamic figure of Irish radical cultural circles of the early twentieth century, helped the two men, whom she referred to as ‘the boys’, in the early days of the Gate. Born in France to a French father and a mother from Wexford, she married Irish republican Fred Cogley in Chile in 1911. Together, they returned to Ireland, where both became part of a cultural milieu with republican sympathies.

You can listen to Toto Cogley recalling ‘the boys’ and the origins of the Gate in her softly accented English for this 1958 broadcast.

Motley, the journal of the Gate Theatre, 1932

And so here we are, our journey finished outside the Gate, having traversed a long street, a century and several continents.

There are few corners of Dublin city untouched by a similar history of migration, one that extends far deeper into the past than most assume.

It’s a history worth celebrating at times, but always one worth remembering.

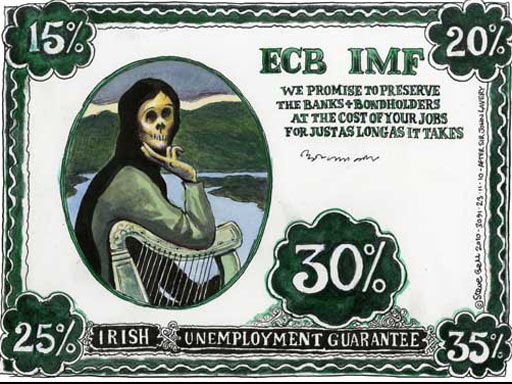

Irish fascists tell a story of Ireland and Irishness that narrows horizons to eradicate compassion. The real history is more diverse than they could ever imagine. Yet just as dangerous – because it appeals to more common liberal sensibilities – is the overly convenient story of unimpeded Irish ‘welcomes’. That story is simply wrong. Racist ideas and movements have a long history in Ireland too. It is the task of us all to ensure those same political forces don’t have a future.

You don’t get to be racist and Irish

You don’t get to be proud of your heritage,

plights and fights for freedom

while kneeling on the neck of another!

You’re not entitled to sing songs

of heroes and martyrs

mothers and fathers who cried

as they starved in a famine

Or of brave hearted

soft spoken

poets and artists

lined up in a yard

blindfolded and bound

Waiting for Godot

and point blank to sound

We emigrated

We immigrated

We took refuge

So cannot refuse

When it’s our time

To return the favour

Land stolen

Spirits broken

Bodies crushed and swollen

unholy tokens of Christ, Nailed to a tree

(That) You hang around your neck

Like a noose of the free

Our colour pasty

Our accents thick

Hands like shovels

from mortar and bricklaying

foundation of cities

you now stand upon

Our suffering seeps from every stone

your opportunities arise from

Outstanding on the shoulders

of our forefathers and foremother’s

who bore your mother’s mother

Our music is for the righteous

Our joys have been earned

Well deserved and serve

to remind us to remember

More Blacks

More Dogs

More Irish.

Still labelled leprechauns, Micks, Paddy’s, louts

we’re shouting to tell you

our land, our laws

are progressively out there

We’re in a chrysalis

state of emerging into a new

and more beautiful Eire/era

40 Shades Better

Unanimous in our rainbow vote

we’ve found our stereotypical pot of gold

and my God it’s good.

So join us.. ’cause

You Don’t Get To Be Racist And Irish.

Dublin, 23.11.23 : A Few Results of the Racist Riots (Photos by Chris Reid)

Leave a comment