Why Does The Irish Labour Party Seek Fine Gael’s Kiss-of-Death?

In the last days of the 2011 Irish General Election Campaign Labour Party leaders and spinners are warning that the voters might choose a Fine Gael single party government. Their alternative? : Coalition – Fine Gael’s Enda Kenny for Taoiseach, Labour’s Eamon Gilmore the Tánaiste – that’s the message.

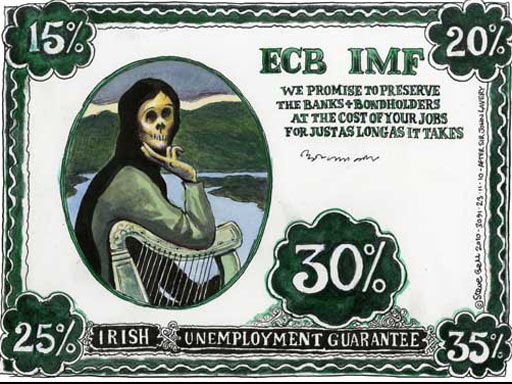

SIPTU leader Jack O’Connor, for example, claims “that a coalition government would be far preferable as the country imposes spending cuts as part of its EU and IMF bailout.

“If you look at the lessons of history, they (Fine Gael) haven’t been in government on their own since 1927 when their predecessor Cumann na nGaedheal was in government,”….

“They pursued policy which resulted in economic stagnation for 60 years. And that’s the kind of policy that’s being advocated by both of the centre-right parties at the present time.”

http://uk.reuters.com/article/2011/02/15/ireland-politics-union-idUKLDE71E2C620

First – is a single-party Fine Gael government possible or likely?

We will know for sure on Saturday February 26 – at the time of writing, if the polls are right, a single party Fine Gael government is possible but unlikely.

A second factor is political – many Fine Gael backers, for example the former party leader Garret FitzGerald, argue that coalition with Labour is a better tactical option for this right-wing party.

“Even on optimistic assumptions, Fine Gael is very unlikely to secure an overall majority. So, to secure and thereafter to hold on to power for a five-year term, the party would need support from some others. Micheál Martin has offered conditional Fianna Fáil support – if Fine Gael adhered to Fianna Fáil policies – but that would not seem to provide a secure basis for a five-year government.

Alternatively, Enda Kenny could be elected taoiseach with the support of some Independents and perhaps the abstention of others. But that might also fail to provide the kind of solid support for a Fine Gael minority government that will need to take a whole range of extremely unpopular measures.

The only other government likely to be available would be a Fine Gael-Labour coalition, the post-election negotiation of which has not been eased by the nature of the campaign to date – although Labour has recently been stressing the continuing feasibility of the two parties agreeing a programme for government.”

http://www.irishtimes.com/newspaper/opinion/2011/0219/1224290287394.html

Would a 2011 single party Fine Gael government be substantially different from a Kenny-Gilmore coalition? What would happen to Labour and its left-wing rivals?

Joe Higgins of the United Left Alliance argues very persuasively that “In the final analysis however both parties’ programmes, like Fianna Fáil’s and the Greens’, agree that working people, the unemployed, students and anybody who depends on public services should bear the brunt for this crisis in the coming years.”

Jack O’Connor says if you “look at the lessons of history” we have not experienced a single party Fine Gael government since 1927 – more than 80 years ago – very true.

Looking “at the lessons of history” in more detail – the practical lived experience of generations – tells us a story Jack O’Connor and the Labour Party leadership does not want us to hear – over and over coalition with the right in Ireland has been disastrous for the left and the wider workers’ movement.

Since 1948 Fine Gael has only governed in coalition with other parties, usually Labour – which is then, in Mick O’Reilly’s words “hammered by the electorate” :

“For years, Labour has acted as a prop for one or other of the two main conservative parties. The debate after every election seems to centre on how many ministers and junior ministries Labour will get. Labour can appoint its own people to boards and quangos just as Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael do and then at subsequent elections Labour is hammered by the electorate. This historical fact seems to be forgotten once government negotiations begin, and could lead one to believe that the lure of the ministerial Merc is just too much for the Labour leadership.”

“The Labour Party should turn a deaf ear to the coalition blandishments of the two major parties”, Mick O’Reilly, Irish Times, Friday August 25 2000 [at that time Mick O’Reilly was Regional Secretary of the Amalgamated Transport and General Workers’ Union, forerunner of today’s UNITE Union]

All the above shows that the “Coalition or Fine Gael Single-Party Government” debate which Jack O’Connor and the Labour leadership promotes is a charade.

So, why are they doing it?

Paddy Healy examines the nature of the Labour Party, in a debate with Desmond FitzGerald of Fine Gael on the politicalreform.ie website –

it is worth quoting in full :

“Paddy Healy says:

You are correct about the POLICIES of the Labour Party. It is true that the reason it is losing votes is that its policies are “nor left enough”

But you are incorrect to classify the labour Party as similar to the British Lib Dems. The lib Dems or “Whigs” are an avowedly capitalist party which historically lost out to the Tories as the main political representative of British Capitalism. The Irish Labour Party was formed by the trade unions (ITUC Congress Clonmel 1912).Even to-day the main Irish Labour movement Organisation SIPTU (formerly ITGWU)is affiliated to it as are many Irish trade unions including the Irish Branch of UNITE. Similarly the main UK Trade Union UNITE is affiliated to the British Labour Party. The British and Irish Labour Parties are members of the Socialist international and the socialist group in the EU parliament. Because of the renegacy of the Irish labour leadership in the War of Independence it has always been a stunted party. These roots are not an excuse for the shameful policy of its leadership. Because of its historical roots and its links to trade unions it is perceived by the population as the political representative of organised Labour in Ireland EVEN BY PEOPLE WHO DON’T VOTE FOR IT. It has a different social base to Fianna Fail and the British Lib Dems. It is a mistake to characterise parties solely in accordance with the policies of their leaderships. Fianna Fail had a very “left wing” policy in the thirties. It ,however, remained a capitalist party, albeit of the Bonapartist variety (eg Peronism, Gaullism). The Labour party is a party of the left with a right wing compromising leadership. A coalition of Labour, Sinn Fein and left TDs would have a different character to a coalition of Fine Gael, Sinn Fein and the left. You think a coalition of Fine Gael and Sinn Fein is improbable? Remeber Clann na Poblachta. Sean McBride, its leader, was a former chief of staff of the IRA. The depth of the Irish crisis is such that literally anything could happen!”

Finally two documents from the archives put together by John Meehan :

1.

THE IRISH LABOUR PARTY –

A COALITION PARTNER FOR ALL OCCASIONS

–April 12, 1996

2.

THE CRISIS INSIDE FIANNA FÁIL

Coalition and the Irish Left

– Socialist Republic, October 1982

=====================================================

THE IRISH LABOUR PARTY –

A COALITION PARTNER FOR ALL OCCASIONS

A Fianna Fáil/Labour coalition government was formed on January 26 1993 in the 26 County part of Ireland. In the winter of 1994, following a series of by-election and European Election reverses, this government collapsed and Labour went into coalition with its usual partner Fine Gael. The Democratic Left, led by Proinsias De Rossa, was added to guarantee a Dáil majority.

The last statewide General Election in November 1992 was a disaster for both Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, the 2 traditional Bourgeois Parties. Both went down to a humiliating defeat. Labour took its highest ever share of the vote, doing particularly well in Dublin with 26%.

When the Dáil reassembled in December no candidate for Taoiseach could secure a majority, and the outgoing FF minority government continued in an “acting” capacity.

Labour first negotiated with Fine Gael, its normal coalition partner. From 1932 to 1989 the pattern was either FF governing alone, or Labour making up the numbers (with others if necessary) to allow the other main right wing party, FG, to govern. The 1989 government was FF’s first coalition. Charles Haughey’s partners were the Progressive Democrats (themselves a split from FF led by Des O’Malley). Many people thought after the November 1992 Election that the old certainties would return and a right wing Labour leadership would once again take the kamikaze path of coalition with the vampire of bourgeois politics, Fine Gael.

Immediately after the Election Labour did negotiate with FG. Party leader Dick Spring sought 2 conditions rejected by FG :

An FG/Labour/Democratic Left coalition (with the support of left Independent Tony Gregory and Trevor Sargent of the Greens, this was enough for a bare majority). FG insisted on a FG/Labour/PD’s coalition.

Spring insisted on sharing the office of Taoiseach with FG, rotating it every 2 years. FG said No, as did the PD’s.

From the Labour Leadership’s point of view, these were not the real reasons for avoiding a coalition with FG. Once the talks with FG broke down, Spring did a deal with FF leader Albert Reynolds, and the “principle” of rotating Taoiseach was forgotten. Also, there was no mention of bringing the DL into the coalition.

The negotiations with FG leader John Bruton were conducted in a very bitter spirit. Labour had almost been wiped out during their de facto permanent coalition with FG from 1970 to 1987. Spring did not fancy another bite from the FG vampire (In 1987, following the collapse of an FG/Labour Coalition, Labour leader Spring only held his seat with 4 votes to spare – this followed a “targeting” of Spring’s seat by his “partners” Fine Gael).

It was easier, as a cosmetic Public Relations exercise, to paint up the FF/Labour government as something “new”.

In Labour circles this was not a “Coalition” – it was a “Partnership Government”.

Labour avoided “Bad News” Ministries like Finance and Justice.

Spring took the media-friendly Foreign Affairs post, and souped up the Tánaiste post.

Former anti-coalitionists were given Ministries or Mini-Ministries (Michael D Higgins, Mervyn Taylor, Emmet Stagg) so any threat of opposition to the government’s right wing policies coming from the party’s traditional left is almost eliminated.

The real reasons for the deal with FF begin with numbers. The FF/Labour government’s parliamentary majority of 35 seats was the largest in the history of the State [99 seats against a combined opposition of 64 (2 vacancies existed at the outset : Mayo West and Dublin South-Central; eventually FF lost the Mayo seat to FG while Labour was humiliated by the DL victory in Dublin South-Central).

Labour got its increased support because it was seen as an anti-government left force. This, for example, is an extract rom Dick Spring’s speech in the Dáil during the November 5 1992 debate on the “No Confidence” motion that brought down the FF minority government :

“Given these three things – the low standards exemplified by past and present members of the Government; the policy of forcing the most vulnerable members of our community to carry the burden of financial adjustment and modernisation; and the undermining of some of the country’s most important assets – it must surely be considered amazing that any party would consider coalescing with them” (Irish Times, December 18 1992)

Labour workers in both Dublin North-West and Dublin North-East stated they got an anti-Fianna Fáil vote. More than one canvasser was told in traditional FF areas that Labour was getting the Nº1 this time, but not to come back if there as a coalition government. In Dublin South-Central, where a by-election was caused by the resignation by FF TD John O’Connell, problems mounted. FF wanted a transfer deal. Labour TD for the area Pat Upton opposed it. Why? Because, in his own words “90% of the people who gave me a Nº1 voted against FF with their lower preferences”. So, what mandate did Upton have for supporting the coalition……?!?

It did not take a genius to work out that Labour’s entry into Coalition with FF was fraught with danger for them. Once the realisation sank in that, despite the PR hype, this government represented more or less exactly the same as the old shoddy FF/PD’s Coalition, a mighty backlash was unavoidable. The big Dáil majority was a sort of insurance policy against this happening – a big number of the 22 backbench Labour TD’s either voted against the Government or abstained on high profile issues (for example the savage cuts in Aer Lingus), and the Coalition remained in office. These demonstrations of mild parliamentary defiance were not a serious worry to the Labour leadership – all the TD’s who broke the Aer Lingus whip were re-admitted into the Labour party a few months later. One of them, Joe Costello, was even elected chairperson of the parliamentary party.

LABOUR – A PRODUCT OF THE PRE-PARTITION POLITICAL SYSTEM

The Labour Party from the outset based itself on the socio-economic illnesses of Ireland, cutting these off from their political source, which they left to the “constitutional politicians” and Republicans.

They abhorred the stress laid on the North and consequently won a large sector of ex-Redmondite (Home Rule) support in the 1920’s. These voters saw both Fianna Fáil and Cumann na nGaedhal as different brands of Republicanism and therefore sought a third choice.

In the April 1977 issue of the Economic and Social Review, Tom Garvin analysed Labour’s support historically and found that it was never an urban party, but a rural one concentrated in the Eastern and Midlands region. “Its attitude on the National Question was uneasy” he says “The Irish Labour Elite was secularist…and British in outlook and in many cases origin”. He also says that the LP was very much a product of the pre-partition political system. This explains their support in the “Pale” outside Dublin and in the garrison counties of the Midlands. In the border areas the LP between 1923 and 1934 got a mean vote of 2% stretching from 0 to 7%. FF got 30-53% of votes in these areas with C na G taking 12-39% of the votes.

The only exception to this trend was 1943 when National Labour, an ITGWU inspired split led by William O’Brien, polled 11.3%.

Until their expulsion from the party, the Militant (and others who favoured an orientation to the Labour Party) regularly argued that the working class would inevitably turn to Labour. History is against this type of approach : examine the only example of the fusion of the National and Socio-Economic questions at a parliamentary level. This fusion, in the late 1940’s, led to the establishment of a new party Clann na Poblachta. In other periods it has led to a split in the Labour vote with some grimacing and voting Labour and others grimacing and voting FF. Since late 1992 (the experiences of FF/Labour and FG/Labour/DL coalitions) the Labour vote has collapsed to the DL (Dublin South Central and Cork North Central by-elections), to the Greens in the Euro-Elections.

After the formation of the FG/Labour/DL coalition there was a disturbing swing to a right wing independent candidate in the Wicklow by-election (Mildred Fox), a decay of the DL and Labour votes, and a strong showing also for the ex political prisoner Nicky Kelly (running as an independent). Joe Higgins of Militant benefited from disillusionment with Labour in the April 1996 Dublin West by-election.

Any increased awareness of the “National” issue usually accounted for some of Labour’s losses, for example in the 1977 Election. In late 1976 The IRA successfully killed the then British Ambassador Ewart-Biggs. The FG/Labour government declared a “State of Emergency”. This provoked constitutional turmoil – President Cearbhall Ó Dálaigh blocked and delayed the passage of new repressive legislation. O Dálaigh then resigned his post in protest at public attacks on him by Government Minister Patrick Donegan (the “thundering disgrace/fucking disgrace” speech to an Irish Army parade). At the same time the Labour Left led by Matt Merrigan and Noel Browne publicly campaigned against the government’s repressive legislation. In the subsequent June 1977 General Election Merrigan and Browne ran independent campaigns, pulling in substantial support. The main winners from this humiliation of the FG/Labour coalition were Fianna Fáil.

THE LATE 1960’s

The late 60’s was a period of expansion for Irish capitalism. This growth was the high-point of the Free Trade policy initiated by Lemass in 1958 and eagerly anticipated Ireland’s entry into the EEC.

The policy of protection in the 1930’s brought with it the nationally minded petty bourgeois entrepreneur as well as preventing the further starvation and emigration of thousands of small farmers. But the national economic growth could not be sustained because of Ireland’s domination by British Imperialism and the fact that much of the most potentially prosperous industry existed in the 6 Counties – under direct British control.

But just as the 1930’s economic policy fostered certain strata of Irish society so too did the Free Trade Area. A new breed of intellectuals, bureaucrats and technicians dominated this new industry. They adopted the political traditions of British liberalism, prided themselves on their outward looking viewpoint, on their secularism and their complete antipathy to the National Question.

They visualised Ireland falling into the political divisions that characterise Britain and Scandinavia – the Conservative/Labour divide. In practice this meant abstracting themselves from the central question in Irish politics – the National Question. In fact just as this stratum was orienting itself politically (1968 -1970) a new and internal phase of that struggle was opening, particularly in the 6 Counties.

The LP was the natural historical choice of this stratum. It was proven as the party which did sully its hands with “the North”, and which represented their cosmopolitan views. This stratum was shocked by the Arms Crisis and its effect on the FF Cabinet in 1969-1970.

Tempered by the short-term boom of the 1960’s and the influx of these cosmopolitan radicals the LP turned left – adopting the slogan “The Seventies will be Socialist”.

Members of the LP in the South were involved in the mobilisations of the time (e.g. Dublin Housing Action Group, Anti-Apartheid Movement and GRILLE, the Radical Christian Movement).

Labour began to attract another kind of member, young humanistic socialists, who saw the LP as the only alternative to FF and FG. These young people were not part of the revolutionary tradition of the Labour Movement but did represent the anti-authoritarian socialism so prevalent in the 1960’s Youth Culture. It was to this audience that Brendan Corish stated he would retire to the back benches rather than participate in a coalition with FG.

THE LABOUR PARTY IN THE 1970’s

In 1971 the LP appeared briefly to be capable of impressing significant sections of the working class who held all the optimism about the future their leaders encouraged. But even at this point, the political links of the LP with the Trade Unions were practically non-existent.

A number of far left groups which were active in the LP at the time (the most prominent being the League for a Workers’ Republic (LWR)/Young Socialists (YS) attempted to unite the most progressive sectors of the LP with similarly minded people outside it. This was the Socialist Labour Alliance (SLA).

The prominence of the National Question was reflected in the narrowly defeated proposal to call the grouping the Socialist Republican Alliance.

The LP leadership quickly moved against the SLA by using the party constitution, stating no member of the LP could belong to another organisation. Instead of beginning a political fight on the right of different currents of opinion to exist in the party the SLA counter-manoeuvred by claiming that it was not a party but a local alliance. The undemocratic procedures of the LP went unchallenged leaving a real political confusion about the methods adopted by the party Head Office.

When the SLA left the LP it took a small number of militants with it who remained politically active. But a number of things should be pointed out :

1. Because the SLA was conceived as a grouping to work within the LP, and because its orientation was electoralist, it could not maintain under its banner the numbers of militants it originally attracted to the LP.

2. The left groups in the SLA had the major perspective of winning recruits, rather than building an alternative democratic Labour Party with roots in the organised Labour Movement.

THE EFFECTS OF THE 1970’s DOWNTURN

The effects of the downturn on the political struggle and of the economic recession showed the Labour Party up as the amalgam it really was (and is). In the debate on coalition at the 1973 Conference, 3 positions were upheld – those opposed to coalition per se, those who wanted to demand “key industries” as the price of their participation in government, and those who favoured coalition at any cost. It was the latter who won the day showing the right wing stance of most of the delegates. At the same conference Conor Cruise O’Brien received a standing ovation for decrying the Provisional IRA as the main cause of the violence in the 6 Counties.

The LP is a clear example that any radical force which is not against British occupation and partition will get sucked into more and more conservative policies, as time goes on, as the Liberal O’Brien called for more repressive legislation and even the censorship of letters in the bourgeois press.

Throughout the period of coalition the Militant Tendency remained in the LP announcing that the coalition would show up the inefficiency of the Fine Gaelers and strengthen the LP as the party of the working class, the only possible party they would turn to. Instead the 1977 elections showed the LP to be the only national party which (proportionately to the number of new voters) lost votes. The party which gained most votes, notably in working class areas, was Fianna Fáil, sociologically the party of the working class.

SOCIAL DEMOCRACY IN IRELAND

The importance of a classical Social Democratic Party is that it gives political expression to the economic organisations of the working class – the Trade Unions.

Historically this was never the case in Ireland. The links which existed were purely formal, primarily consisting of a one-way flow of funds from the Trade Unions to the Labour Party. This fact is shown in the very low representation of Trade Unions at LP conferences.

The Irish LP has been further marked by the heterogenous nature of its TD’s. In the 1970’s Dan Spring (father of the current Labour Leader) and Limerick’s Stevie Coughlan represented a right wing sector of the population, while Mary Robinson and Conor Cruise O’Brien appealed to a narrow stream of the liberal intelligentsia.

A solid bloc of rural TD’s (Joe Bermingham [Kildare], John Ryan [Tipperary North], Dan Spring [Kerry North]) depended mainly on constituency work. A few maverick TD’s in Dublin with a tinge of urban radicalism (John O’Connell, Noel Browne) completed the picture. Their votes were largely personal.

Of these, only Noel Browne ran a social democratic campaign. Spring and Coughlan were hard to distinguish from FF TD’s, and were to the right of them on many issues. O’Brien and Robinson were in Labour only due to the absence of a Liberal Party.

Finally there is a powerful electoralist effect on Labour as the third party in the State. The LP is a governmental party with no hope of governing alone. Yet it has gradually centred itself solely around its parliamentary base. That poses formidable problems for opposition currents within it, particularly if a threat of a split arises.

Traditional Labour left wing currents concentrated on a governmental programme. Its only difference with the leadership was in the more radical bent of its proposals. Accordingly it is always necessary to fight for any such currents to get directly involved in the class struggle.

SOME PARALLELS WITH THE PAST

The electoral recovery of the Labour Party between 1987 and 1993 is quite remarkable.(1)

It is sociologically significant because the level of support attained in urban areas is only equalled in the 1960’s. But, as we know, the 1970’s heralded an equally deep drop in the party’s support and by 1987 the party barely survived as a real parliamentary force (6.4% of the Statewide vote, 12 seats). In fact the LP got less support than the Progressive Democrats, and dropped to being the fourth largest parliamentary party.

Plenty of signs indicate that Humpty Dumpty Labour is heading for another big fall – and Spring’s men and women will be trying to put together an awful lot of pieces.

Labour has no electoral mandate for Coalition with either Fianna Fáil or Fine Gael. The vote it got was anti-government, anti-Fianna Fáil, and in a very soft way anti the right wing trend of recent years. But it was not very positive or coherently left wing. There was no noticeably big transfer to the Democratic Left for example.

This means disillusionment is running very deep, shows itself dramatically in elections, and does not have any obvious left wing home to go to. The right wing opposition are preparing to get what they can out of this inevitable debacle.

John Meehan April 12, 1996

Source Material :

Arthur Mitchell’s book “Labour in Irish Politics 1890 – 1930” is an excellent source on the origins of the Labour Party in Ireland, and interested comrades are urged to read it. Most of the background material is taken from a paper written by Betty Purcell for the then Irish Section of the Fourth International, the Movement for a Socialist Republic [MSR] in 1977/78)

Footnote

(1) Of interest, it was predicted since at least the June 1989 Election in articles published in An Réabhlóid and International Viewpoint. when the first signs were just barely visible.

A Final Word :

This document was completed on February 29 1996. It has been altered slightly to take account of the Dublin West by-election held on April 2 1996. The result there – the huge support given to Joe Higgins of Militant – is another sign of the coming electoral collapse of the Irish Labour Party. It is a deserved price for the politics of coalition with right wing bourgeois parties.

========================

THE CRISIS INSIDE FIANNA FÁIL

Coalition and the Irish Left

Introduction :

Between June 1981 and November 1982, no Dublin Government was able to rely on a stable majority : three elections were needed before Fine Gael was able to form a Coalition Government with the Labour Party. The balance of power was held by either small left parties, or independents (most of them left-leaning) : Noel Browne, Jim Kemmy, Tony Gregory, Seán Dublin Bay Loftus, Neil Blaney and the Workers’ Party. In addition, two abstentionist H-Block political prisoners – Kieran Doherty in Cavan-Monaghan and Paddy Agnew in Louth – won seats in the June 1981 General Election.

The next General Election for the Dublin Dáil will be held in May 2007 at the latest : it is possible, but not certain, we could enter a period of governmental instability, when small groups of mainly left-leaning deputies will again hold the balance of power.

The article below, published in the October 1982 edition of “Socialist Republic”, set out the position of People’s Democracy at that time. Some footnotes are added containing additional information.

John Meehan, 30 March 2006

Charlie Haughey’s deals are becoming a legend : the promise to build Knock Airport, the Talbot Deal (redundant car factory workers were guaranteed a full wage until they regain full jobs in the run up to the June 1981 General Election)1, and the agreement made with Tony Gregory (TD for Dublin Central) in order to secure a voting majority for Fianna Fáil after the indecisive February 1982 General Election are coming under constant attack and ridicule in the mass media. This was started by the Kildare Fianna Fáil TD Charles McCreevy just before the June 1981 election. McCreevy proposed the motion of no confidence in Haughey at the October 6 1982 meeting of the Fianna Fáil parliamentary party. Haughey survived by 58 votes to 22. Are we about to see the end of the Haughey legend?

Fianna Fáil – the Favourite Party of the Ruling Class

The motion of no confidence and the resignation of two ministers (Des O’Malley and Martin O’Donoghue) has prompted a lot of speculation about a split in Fianna Fáil. No one should do this without carefully reviewing the history of the past 50 years. The Irish political landscape is littered with the corpses of failed politicians who rashly broke the Fianna Fáil whip. The party’s record speaks for itself.

Since 1932, Fianna Fáil have been the governing party for 39 out of 50 years. They have won 13 out of 17 General Elections.2 On the rare occasions Fine Gael dominated coalitions have come to power they have never held on longer than one term in office.3

When Fianna Fáil first took over the government in 1932, they did not have the direct support of big business. Sixteen years in office changed that. A “national bourgeoisie” grew behind high tariff barriers until the late 1950’s. Saturation point was reached. In the early 1950’s, Industry Minister Seán Lemass was warned by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) not to extend the programme of national economic independence by nationalizing the banks. Chronic stagnation ate into the economy. A new course was necessary : free trade replaced protectionism. Legislation prohibiting foreign capital from controlling Irish firms was abolished. The floodgates were opened first to British Capital (the Anglo-Irish Free Trade Agreements) and gradually to Foreign Capital in general (accelerated by membership of the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1972).

Fianna Fáil not only survived the transition but also strengthened its political control. Folk memories of the 1950’s obscured the rather unimpressive results of the free trade policy. “The Soldiers of Destiny” spent 16 uninterrupted years in government between 1957 and 1973. This eroded Fianna Fáil’s brand of populist nationalism. Serious conflicts had occurred between the nascent national bourgeoisie and British Imperialism during the 1930’s and 1940’s [the tariff barriers, the economic war, the campaign for self-sufficiency, development of native natural resources (for example Bord na Móna, The Sugar Company), slogans such as “burn everything British except their coal”, neutrality during World War II, and so on]. The 1950’s “turn” implied a friendlier ideological attitude towards imperialism. Decades of suppressing republicans fighting for Irish Unity encouraged openly pro-British trends inside Fianna Fáil.

The Northern Crisis

The eruption of the Northern Crisis in 1968 threw a spanner into the works. A wave of support spread throughout the South. The Fianna Fáil cabinet took desperate measures to try and control the situation. Charles Haughey became directly involved in an attempt to run guns to the North for defence of the Catholic minority after the Derry and Belfast riots of August 1969. Later when the situation slightly stabilised the Fianna Fáil Taoiseach Jack Lynch sacked the main gun runners. Despite a sensational Arms Trial where Haughey was acquitted and the evidence of the star prosecution witness James Gibbons (Minister for Defence at the time of the gun-running attempt) was rejected by the court, Fianna Fáil stayed intact.

A second spanner was thrown into the works by the recessions of the 1970’s. When Fianna Fáil opened the cupboard to throw a few crumbs to the voters, they began to find it was bare. Today the bosses kick up a hue and cry about Haughey’s “deals”. They have been echoed by the minority of 22 who have no confidence in Haughey as leader of the Fianna Fáil party. It is worth re-membering that “deals” did not start with Haughey.

All wings of Fianna Fáil offered “deals” during the 1960’s : it was the cement binding together the upper echelons of the ruling class and the party’s very broad social base in the working class, petty bourgeoisie, and the small farmers. Fine Gael by contrast had a narrower social base, was confined to sectoral interests like the big farmers even within the ruling class, and possessed a ramshackle political machine.

The 1977 Manifesto

The June 1977 General Election gave Fianna Fáil its second highest ever share of the popular vote (just short of its 1938 score). This spectacular success owed a lot to the promise of an economic bonanza : remember the claim that unemployment would be completely abolished! The architects of that plan are today’s anti-Haugheyites (Senator Eoin Ryan, Martin O’Donoghue, Des O’Malley and George Colley). The inevitable failure to deliver on these promises caused a slump in Fianna Fáil’s popularity and the backbench TD’s were terrified of electoral disaster. Haughey took the leadership in 1979 after Síle DeValera, Bill Loughnane and others paved the way by attacking Lynch for his conciliatory attitude to the British government over the North. A private conspiracy was also hatched involving people like Ray MacSharry and Seán Doherty : they owe their present ministerial status to Haughey’s successful leadership bid. Charlie McCreevy also backed the Haughey challenge : he got no ministerial job and he switched sides.

Haughey continued in the same vein as the 1977 manifesto : he juggled with the public finances in order to put off the worst austerity until after the June 1981 General Election. Practical collaboration with Britain was deepened but a revival of nationalist rhetoric was encouraged. Big business began to switch to Fine Gael for the first time since the 1940’s.

The indecisive election results of June 1981 and February 1982 deepened Haughey’s difficulties. John Bruton’s Fine Gael budget failed because the austerity proposals frightened the handful of TD’s who held the balance of power. After Haughey returned to power in March 1982, his budget made some modifications to Bruton’s budget. Inside Fianna Fáil a dirty fight developed between Haughey and Senator Des Hanafin (a big business supporter of the Colley /O’Malley dissidents) over control of Fianna Fáil funds. Haughey eventually won the struggle but was in danger of losing all support from big business.

Despite the danger of losing electoral support Haughey turned around at the beginning of August and carried out the harsher austerity programme demanded by big business. Ironically just when Haughey was settling his differences with big business, and clarifying to the working class that his is no different to Fine Gael in the long run, a new crisis has erupted inside Fianna Fáil.

A National Government?

The programme put forward by the dissidents is still much more consistent with the interests of big business than Haughey’s activities. The problem is that the indecisive election results have not allowed the mobilisation of a stable parliamentary majority behind the offensive desired by the ruling class. Haughey had hoped to do this by winning an absolute majority for Fianna Fáil in the next General Election, which is likely to occur very soon. The new flare-up inside the party obviously minimises the chances of Fianna Fáil success. At the same time, there is little likelihood of a Fine Gael dominated government winning a majority either. First of all, even traditionally pro-coalition wings of the Labour Party want no alliance with Fine Gael in the near future. The drop in the Labour vote from 17 per cent in 1969 to 9.9 per cent in 1982 is a very persuasive argument against coalition for even the most die-hard right-wingers who favour Coalition!4 Secondly, it is clear that Fine Gael has no chance at all of forming a government on its own. Last February they won 37 per cent of the national vote, their highest ever but too far behind Fianna Fáil’s score of 47 per cent. No wonder that influential sections of big business are encouraging talk of a “National Government”.

There are grounds for believing that this is the project of the anti-Haughey minority inside Fianna Fáil : certainly, they regard it as one of their options.

They might do so without a General Election : 63 Fine Gael TD’s, plus 22 TD’s from Fianna Fáil, plus a rump from the Labour Party. If they seriously believed they could topple Haughey, their timing was insanely reckless. If McCreevy had succeeded, Haughey would have remained Taoiseach until October 27, when the Dáil reconvened after the summer recess. Assuming that ex-leader of Fianna Fáil Haughey would have generously (and uncharacteristically!) agreed to bring this date forward, the new Fianna Fáil leader (Colley or O’Malley) would not have been guaranteed a majority in the Dáil : Fianna Fáil have 81 TD’s out of 166, Haughey’s friend John O’Connell having no vote as Ceann Comhairle, so they are two short of a majority. Tony Gregory and Neil Blaney are their only hope of winning such a vote. Gregory said he would not vote for a new Fianna Fáil candidate for Taoiseach, and Blaney suggested McCreevy and company should be taken away by men in white coats! He was not far off the mark : Fianna Fáil would probably have lost such a vote and then would have been forced into a General Election with Haughey as a “lame duck” Taoiseach and another individual the “leader” of Fianna Fáil. Fianna Fáil constituency organisations were rapidly and ruthlessly mobilized by Haughey before the “no confidence” vote : they came out very strongly against the dissidents. It takes little imagination to predict their reaction when faced with the pleas of the anti-Haugheyites for a nomination to fight the General Election.

A General Election is of course likely anyway. Bill Loughnane’s death and James Gibbons’ heart attack has reduced Fianna Fáil’s Dáil strength to 79, only one more than Fine Gael and Labour. Haughey’s future is not in the hands of Gregory and Blaney, but in the hands of Jim Kemmy and the Workers’ Party’s three TD’s.

McCreevy and his fellow conspirators are not fortune tellers and they could not have foreseen the sudden reduction in Fianna Fáil strength to 79. Nevertheless, if they did not foresee that their attempt to topple Haughey was doomed they won’t last much longer inside Fianna Fáil or Irish bourgeois politics. The only possible alternative explanation is that they consciously plan a new Government with Fine Gael.

Government Instability and the Irish Left

One way or another the governmental instability will not last indefinitely. What does this mean for the Irish Left?

At the moment the strategy put forward by the parliamentary left amounts to supporting either a Fine Gael/Labour Coalition or Fianna Fáil on the grounds that one or other is a “lesser evil”. The Workers’ Party and Tony Gregory consistently vote for Haughey on the grounds that the brutal Bruton alternative would be worse. We have now had six months to review this policy and the results are negative. It is quite astonishing how timid the Workers’ Party and Gregory have been : for example, they could have brought in a bill to abolish capital punishment since there is a formal parliamentary majority in favour of the measure : only Fianna Fáil are opposed and Fine Gael introduced such a measure during its brief period of government in 1981.

The disastrous result has been to sow illusions in the working class that the worst effects of austerity could be fended off by slick parliamentary manoeuvres. Thus, Haughey encountered relatively little organized opposition when he announced the public sector pay freeze in August. Furthermore, there was never a big difference between the Fianna Fáil austerity and the Fine Gael version. True MacSharry did not impose VAT on shoes and he did not tax social welfare benefits : he compensated by deducting money from workers through more punitive income tax rates.

When the Labour Left opposed coalition in the 1970’s they always said the best policy would be no support to either of the big bourgeois parties. Noel Browne lost his nerve when faced with the chance to carry out this policy in June 1981. The Workers’ Party, Tony Gregory, and Jim Kemmy have done the same. In the new General Election, it will be necessary to assert the need for independence from the two main ruling class blocs. People’s Democracy only has “confidence” in the working class.

JOHN MEEHAN

Socialist Republic, October 1982

1 The workers were members of the Amalgamated Transport and General Workers’ Union (ATGWU), led by the late Matt Merrigan, who died on June 15 2000. The Talbot settlement is discussed by Matt Merrigan’s successor in the ATGWU, Michael O’Reilly, in “Matt Merrigan, a Marvellous Legacy”, Red Banner Nº8, November 2000

2 We can bring the story up to date (March 2006) : Since 1932, Fianna Fáil have been the governing party (sometimes in coalition) for 56 of the last 74 years. They have won 18 out of 23 General Elections.

3 This is still true The FG led coalitions of 1982-87 and December 1994 – June 1997 lost the following elections.

4 I underestimated the kamikaze style willingness of the Labour Party leadership to enter government with Fine Gael after the November 1982 General Election. In the following election – November 1987 – the Labour vote shrank to 6.4 per cent, its lowest share of the state-wide vote for 50 years. They crawled back to the Dáil with 12 seats out of 166 – party leader Dick Spring only held on by four votes in North Kerry, and many of his colleagues were very lucky to win a seat – for example Michael D Higgins in Galway West.

Written by tomasoflatharta

Feb 23, 2011 at 12:32 pm

4 Responses

Subscribe to comments with RSS.

I’m afraid that I don’t really find Paddy Healy’s case at all convincing. It is an ahistorical line of argument, which doesn’t take into account the dramatic changes which have taken place at every level of the Labour Party since the late 1980s.

It isn’t simply that the leadership pursues a right wing policy any more. As I’ve pointed out here before, there is no alternative left party leader. There is no left member of the front bench or prospective member of the front bench. There isn’t even one left wing TD. Not one. Leaving the parliamentary party aside, there are no left organisations at the rank and file level, no alternative left programmes, no left publications. There isn’t even one branch with a left profile within the party. When it comes to conference delegates, not a single one of them was opposed to coalition with FF/FG in principle when the issue was debated at Labour conference just before the last election. Again: Not one single delegate.

Listening to people on the left posit a distinction between a right wing Labour leadership and an allegedly left wing Labour membership is a little like reading a scholastic on the properties of different choirs of angels. They are talking about forces which exist only in their imaginations.

The Labour Party has a very small membership in the greater scheme of things. It is not a mass party in the sense that most social democratic parties abroad are, or in the sense that Fianna Fail has been here. There is absolutely no evidence to suggest that the views of the bulk of that small membership are anything other than accurately represented by the right wing leadership. Various members will disagree with this or that policy or even this or that coalition policy, but broadly speaking, a very large majority of them are singing from the same hymn sheet.

That isn’t to say that there are absolutely no Labour members with left wing views. There are of course some. But they are neither numerically significant as a constituency, nor strategically placed so as to have the slightest chance of significantly reorienting the party.

If Labour is consigned to opposition (I don’t think it will be and if it is, it won’t be through their own choice), they will in all probability tack to the left a bit, wringing their hands at various cuts. It is vital to understand that they will do so not because of left oppositional pressure from within the party but because it will in cynical terms of electoral calculation the thing to do.

It’s also worth noting that receiving union backing does not in and of itself mean much – the US Democrats being the classic example of a liberal party in large part funded by the unions. Even formal ties doesn’t actually determine the nature of a party, some Christian Democrat parties have union links, notably in Belgium.

Mark P

Feb 23, 2011 at 1:57 pm

Big parties back savage cuts, says left alliance :

http://www.irishtimes.com/newspaper/ireland/2011/0223/1224290628842.html

tomasoflatharta

Feb 23, 2011 at 6:47 pm

To follow up on this:

The Labour Party is a very small party in the greater scheme of things, with circa 5,000 paper members. 1,000 people, a significant majority of the active membership, attended its special conference on Sunday.

The total vote against a sweeping programme of cuts, privatisations and taxes, the most right wing programme for government in the history of the state, was 50.

This isn’t a case of a healthy, left wing, rank and file under a sell out leadership. In the rank and file, the combined forces of those who opposed the coalition for left or leftish reasons and those who opposed the coalition for straightforward reasons of party self interest amounted to 50 people.

The Labour left is a smaller group of people than an organisation like the Workers Solidarity Movement. Talk about appealing to the Labour rank and file is a fantasy on a par with talk of appealing to the angels and saints.

Many people who voted Labour are part of the socialist left’s potential audience. Almost nobody who is actually a Labour activist is.

Mark P

Mar 8, 2011 at 3:11 pm

The Irish Left Review has this interesting looking article : Aspects of the Irish Party System: Labour, the Left, and Coalition politics

http://www.irishleftreview.org/2011/03/10/aspects-irish-party-system-labour-left-coalition-politics/

http://www.irishleftreview.org/2011/03/10/aspects-irish-party-system-labour-left-coalition-politics/ery

Briefly, on one aspect of the debate – we are hoping to publish some research on how Labour Party voters transferred lower preferences to other candidates – both when other Labour candidates were in the race, and when other parties were hoping to pick up extra support. In the past Labour – Fine Gael coalitions were built on high inter-party transfers – thqat is the typical Labour transfered to Fine Gael, and vice versa.

It appears to me that a very different trend emerges from the 2011 general election, after a quick initial looki at the figures.

I start with the elimination of Ivana Bacik of Labour in Dún Laoghaire, where three candidates were still in the race : Mary Mitchall O’Connor (Fine Gael), Mary Hanafin (Fianna Fáil), Richard Boyd-Barrett (People Before Profit / United Left Alliance)

The breakdown was like this

Votes Transferred : 7306

Mary Mitchall O’Connor (Fine Gael), 2554 : 34.82 per cent

Mary Hanafin (Fianna Fáil), 876 11.99 per cent

Richard Boyd-Barrett (People Before Profit / United Left Alliance) 2461 33.68 per cent

Non-Transferable, 1415 20.51 per cent

In other words, the far-left candidate gets one-third of the Labour Transfer, just below the number gained by the Fine Gael runner (total right-wing transfer is FF plus FG equals 45.81 per cent).

I think a similar statistical pattern will be discovered across the state – and it means there is a massive disconnect between Labour Voters – many of whom prefer the hard-left anti-coalition candidate to the party leadership’s governmental spouse – and Labour members, 95 per cent of whom decided that Eamon Gilmore should exchange vows with Enda Kenny – a loving couple!

That is a big change from the coalitions of the 1970’s and 1980’s, and it has big implications for the tactics the United Left Alliance should pursue.

In those days a sizeable left wing inside the Labour Party opposed coalition, but most party voters backed the leadership line. All seems reversed today.

tomasoflatharta

Mar 14, 2011 at 9:59 am